Recently there has been some uproar concerning camels and

the Bible and JK covered it at his nice blog Varnam. According to the

report by Dr. Erez Ben-Yosef and Dr. Lidar Sapir-Hen of Tel Aviv University's

Department of Archaeology mentioned in Varnam, - The origin of the domesticated camel is

probably the Arabian Peninsula, which borders the Aravah Valley and would have

been a logical entry point for domesticated camels into the southern Levant.

The arrival of domesticated camels promoted trade between Israel and exotic

locations unreachable before, according to the researchers; the camels can

travel over much longer distances than the donkeys and mules that preceded

them. By the seventh century BCE, trade routes like the Incense Road stretched

all the way from Africa through Israel to India. Camels opened Israel up to the

world beyond the vast deserts, researchers say, profoundly altering its

economic and social history.

NY Times counters - There

are too many camels in the Bible, out of time and out of place. Camels probably

had little or no role in the lives of such early Jewish patriarchs as Abraham,

Jacob and Joseph, who lived in the first half of the second millennium B.C.,

and yet stories about them mention these domesticated pack animals more than 20

times. Genesis 24, for example, tells of Abraham’s servant going by camel on a

mission to find a wife for Isaac. These anachronisms are telling evidence that

the Bible was written or edited long after the events it narrates and is not

always reliable as verifiable history.

But this article is not going to be anything to do with such

theological and mythological accounts however historic or authentic they may

be. Look at our own Keralolpathi or Kerala Mahatmyam, all written with specific

purposes, nevertheless offering only tidbits of historical value. So this note will

hover around how important the animal was to further trade with India, the very

aspect the TAU article has concluded with.

Another important discussion these days is about the battery

used for hybrid and electric cars. They say rightly - If only it could be made

more reliable and higher capacity, these vehicles could then become popular and

run long distances, reducing our dependence on fossil fuel! Well it was the

same many millennia ago when the horse and the donkey were the vehicles for

transport. They too just could not be used for long distance travel without

regular supplication and refueling. Interesting, right? That was about the

juncture when a super-efficient camel and its saddle design saved the day and

stated long distance trade. Let us see how.

One could start here looking at prehistoric animals like the

Protylopus (40 million years ago) which roamed the North Americas and which

perhaps in the centuries which followed, crossed the Beringia land bridge to

move to the Eastern hemisphere. The ones which remained in the Americas perhaps

fell prey to carnivorous animals and the ones which crossed over to the Asian

regions failed to fare better, at least initially. But evolution helps in such

matters and their ability to store large amounts of fluids allowed them to

migrate to inhospitable arid deserts where they multiplied and thrived, by

being far away from the carnivorous lions and other beings which preferred to

live near the wetter areas. As time went by, they found an ally which would

help this slow moving animal to survive, that being the human.

The human being evolved to become a complex creature, for

not only did it want to survive, multiply and do well, it also wanted to

congregate and make its life better by eating a variety of things, wearing

brighter and cooler or warmer clothes, learn all kinds of social and survival

skills and so on. Man was also very inquisitive and selfish in all its

endeavors. In those early forays, especially in the Middle Eastern regions, the

silent companion which aided and abetted the human was the camel, as the

conduit for long distance land trade by becoming the ship of the desert as it

came to be known. Today it is connected sarcastically with the Arab Bedouin,

but it was very prevalent in the Western parts of India and many other places

too.

While the first types were the double humped long haired Bactrian

camels of Asia, the Middle Eastern evolution figured the modern single humped

Dromedary camel. More knowledgeable people opine that this evolution was to

reduce surface area and thus reduce evaporation of moisture - by increasing the

body temperature to reduce perspiration. Anyway the docile and hardy dromedary

(dromados – Greek for running) animal became a friend of the Arab and Asian

nomad, to join goats, donkeys, sheep, dogs, chicken, cattle and so on in his

stable as well as becoming an animal producing food and milk for some others.

It is said that at the outset they were milk producers rather than objects of

transport in Arabia, but eventually they took over from the donkey by about

1500 BC. As Bernstein explains, a single driver herding six animals transported

about two tons of cargo for about 30-60 miles per day, drinking once in three

days, and this gradually increased as saddle technology improved. The Asian

camel became domesticated even earlier, perhaps by 2500BC, but soon its

territory was overtaken by the hardy dromedary cousin and soon the hybrid

variety, supremely capable of trekking long distances and took over the silk

road trade route thriving in the region between Morocco and India, and up all

the way to Western China. In fact its survivability was high and it could even

survive on brackish water.

And this brought about what we know as the caravanserai or

rest stations roughly every 100 miles over the 4,000 mile long Silk Road,

during the hey days of the land trade route. As wiki explains - Most typically a caravanseai was a building

with a square or rectangular walled exterior, with a single portal wide enough

to permit large or heavily laden beasts such as camels to enter. The courtyard

was almost always open to the sky, and the inside walls of the enclosure were

outfitted with a number of identical stalls, bays, niches, or chambers to

accommodate merchants and their servants, animals, and merchandise.

Caravanserais provided water for human and animal consumption, washing, and

ritual ablutions. Sometimes they had elaborate baths.

The main item that traveled westward was of course silk,

while the easterly route had incenses (frankincense and myrrh) from these arid

areas. The objects of trade changed with time and demand as well as

development. Palestine for example produced the prized opobalsam (Myrrh, balm

of Gilead – a sap or oleo resin). That was of course the biggest material of

trade for the people of Arabia and much prized by the people in the west as

well as the east. As a small load was enough to provide a decent profit, it was

easily transportable by the royal road to Rome and also down by the side to the

Red Sea to Aden where it went on ships to India.

So now you know how caravans, convoys or camel trains traversed

these ancient trade routes not as early as 3500 years ago, but somewhere

between 3000-3500 years. As this trade developed,

The Trans Saharan trade became an important one at the turn

of the anno domini or somewhat earlier. The general contention shared by Ilse

Kohler and Paula Wapnish is that the 12-15th century BC is when the

camel got domesticated. However considering Mason’s theory that it evolved in

Arabia around 3,000BC, the period in between needs further analysis. It is also

clear that there were three broad classifications of the dromedary, the beast

of burden or the baggager, the riding camel and the milking camel. It is also

clear that those North African Muslim traders usually set out with their camels

well laden, in a fat and vigorous condition; and brought them back in a bad

state, that they commonly sold them at a low rate to be later fattened by the

Arabs of the Desert (Consider the analogy with second hand cars!).

But let us get back to trade. Everything you see today in

day to day life and take for granted originated step by step, due to a desire

for change, be it food, clothing or life partners. Let us take a look how. It

was as you can see, the desire for exchange of goods and traditions that led to

development of currencies and currency rates. The difference between such rates

resulted in profit and this resulted in the concept of risk, where a trader

decided whether it was worth travelling 4000 miles with a load of expensive

trading goods from one end of the world to the other, braving robbers who

developed the concept of theft, weather and natural calamities (forecasting and

cartography, travelogues). Managers managed the caravans, the procurement and

disbursement of goods and policing came about for the protection of the caravan

routes. Armies and armed personnel were the prerogative of the king and so the

power of the king evolved with the size of the army or quantity of armaments.

The concept of luxury evolved. Agriculture and production of raw material primarily

for trade and not just for own consumption evolved and became a business,

creating the producer and the trader. And as trade volumes and portability

improved, agreements between diverse rulers created alliances to share the

spoils and concentrate power.

In previous articles, we went over a number of subjects set

around the ocean trade, especially the Red Sea and Indian Ocean trade. This

will also look at another kind of ocean trade, the sand ocean trade where the

transport was across the vast Sahara desert (3 million square miles of it),

then the Gobi desert and finally the central Asian Mongol desert. Fittingly the

ship was the camel, when the organized trade started around the 2nd

century AD. It had the Han china on one end, Parthian Persia in the middle -

the westerly connections to the Romans and the Egyptians. The establishment of

the Silk Road made the travel organized and the movement of gold, silk and

spices smooth. As time passed, it became a vehicle for the passage of yet

another commodity – that being religion. I call it a commodity because it was

regulated in its spread and consumption.

The trade groups which were formed were a result of

religious and family associations, just like the Islamic merchant sea

associations or the smaller land trade associations around the south of India.

During those periods it also became a war animal, and the N Arabian

saddle invented around 500BC helped. Even though it was slow compared to a horse,

it was dependable, a specialized breed of riding dromedary could maintain a

speed of 8-10mph for up to 18 hours. During the winter, the camel can travel

fifty days without being watered, while in the hot summer it can traverse

roughly five days without water. A thirsty camel can drink up to eighty liters

of water in one session, and at the rate of twenty liters in one minute.

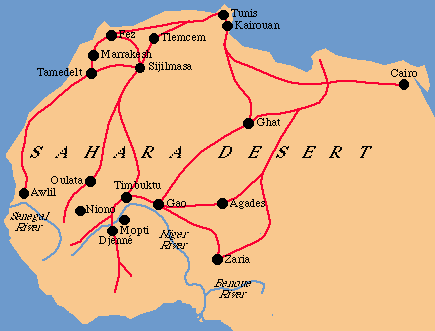

Alistair Boddy-Evans in his article Trade across Sahara

mentions - The sands of the Sahara Desert

could've been a major obstacle to trade between Africa, Europe, and the East,

but it was more like a sandy sea with ports of trade on either side. In the

south were cities such as Timbuktu and Gao; in the north, cities such as

Ghadames (in present-day Libya). From there goods traveled onto Europe, Arabia,

India, and China. Muslim traders from North Africa shipped goods across the

Sahara using large camel caravans -- on average around a thousand camels,

although there's a record which mentions caravans travelling between Egypt and

Sudan that had 12,000 camels. They brought in mainly luxury goods such as

textiles, silks, beads, ceramics, ornamental weapons, and utensils. These were

traded for gold, ivory, woods such as ebony, and agricultural products such as

kola nuts (which act as a stimulant as they contain caffeine). They also

brought their religion, Islam, which spread along the trade routes. Until the discovery of the Americas, Mali

was the principal producer of gold. African ivory was also sought after (over

Indian) because it's softer.

So the real link up was when the Trans Saharan network

linked up with the silk route, mainly due to the Akan gold mining efforts. And

that brings us to Timbuktu. Strange that this place in Africa got connected to English

usage as a place in the middle of nowhere! It was someplace in those days, an

important place, perhaps not today. Its

long history as a trading outpost that linked west Africa with Berber, Arab,

and Jewish traders throughout north Africa, and thereby indirectly with traders

from Europe, has given it a fabled status, and in the West it was for long a

metaphor for exotic, distant lands: "from here to Timbuktu." It

was also a place where rock salt was mined. Gold, sought from the western and

central Sudan, was the main commodity of the trans-Saharan trade. The traffic

in gold was spurred by the demand for and supply of coinage.

|

| Gold Road |

According to the Heilbrun timeline, From the seventh to

the eleventh century, trans-Saharan trade linked the Mediterranean economies

that demanded gold—and could supply salt—to the sub-Saharan economies, where

gold was abundant. Increased demand for gold in the North Islamic states, which

sought the raw metal for minting, prompted scholarly attention to Mali and

Ghana, the latter referred to as the "Land of Gold." By the end of the twelfth century, however,

Ghana had lost its domination of the western Sudan gold trade. (Check Timothy

Insoll’s work for details). But it was the Portuguese discovery of new

sailing routes and trade routes that started the demise of the trans-saharan

trade and decrease dthe importance of African ports and trading locations. The

battle of Tondibi in 1591 destroyed much of the western locales like Timbuktu

and Gao.

Nevertheless, the incense route where Arabian frankincense

and Myrrh which were in high demand, were transported by camels from Hadhramaut

to Mediterranean ports like Ghaza together with shipments from India, was the

most lucrative of all trades. Frankincense and myrrh, highly prized in

antiquity as fragrances, could only be obtained from trees growing in southern

Arabia, Ethiopia, and Somalia. The incense land trade from South Arabia to the

Mediterranean flourished between roughly the 7th century BCE to the 2nd century

CE and involved transport of Indian goods northwards and Arabian goods southwards

to Arabian ports. As Nabataea states - At

its height, the Incense Route moved over 3000 tons of incense each year.

Thousands of camels and camel drivers were used. The profits were high, but so

were the risks from thieves, sandstorms, and other threats. The Incense

Route ran along the western edge of Arabia’s central desert about 100 miles

inland from the Red Sea coast; Pliny the Elder stated that the journey

consisted of sixty-five stages divided by halts for the camels.

For those who are curious, Frankincense the balsamic resin is

Benzoin or the Sambrani we use in Pujas and Myrrh is used even today in

Ayurvedic medicines (a.k.a polam).

And so friends, that was a bit about Camels, without whom we

would not developed. The Trans Saharan road will take over the desert camel

routes, the Silk Road is still there and the sea routes have developed though

fraught with piracy. But the Camel can still be seen and is used in Northwest

India and Arabia, and various other places, though taken over by the four wheeler

when it comes to land trade…

Incidentally there is a tradition (Food Culture in the Near

East, Middle East, and North Africa - By Peter Heine) that Prophet Muhammad

said – who does not eat from my camels is not my people, signifying a religious

connotation to eating camel meat unlike the Jews where both camel milk and meat

are taboo! The reasoning behind this is perhaps evident in the tale narrated in

Nabatean history site about the theft of the Jewish camels by the Arabs.

But there is also this

Sufi saying, 'Trust in God, but tie your

camel first.' You can see that in the days when religion evolved, the motto

sounded right and pragmatic and it does even today, except that some people have

forgotten it and still continue to forget it.

References

A splendid exchange – William J

Bernstein

The Camel and the Wheel Richard

W. Bulliet

Nabataean history http://nabataea.net/camel.html

Cross Cultural trade in world history

– Philip D Curtin

World History: Journeys from

Past to Present - Candice Goucher, Linda Walton

Pics

Wikiimages