I have deliberately been staying away from the topic of Muziris. There is such a lot out there for public consumption and there are many experts working on this subject. So with many contributors on a regular basis covering the history, geography & anthropology of that ancient port, I decided to instead work my way through other confusing chapters of Malabar history. Nevertheless, when a friend Nikhil asked me an interesting question, I dredged a bit into my treasure chest of Indian Ocean trade which has a large collection of books including the Goitein collection and the India book, to get to the appropriate answer.

The question was - Why did the people of the Chera kingdom import Olive oil from Rome? The gist of the answer I gave him was - that the presence of Amphorae actually signified the import of three liquids from broad studies of the ports in the West & East coastal ports, namely Olive oil, Wine and Garum. The consumption of fragrant Italian wine is something we see mentioned in ancient scripts like the ones from the Sangam era – e.g. Manimekhalai& Silapadhikaram. It was imported for local but possibly upper class consumption. It is also concluded that olive oil was never staple in South Indian diet and is an acquired taste which was never acquired into S Indian cooking to date. Garum is a smelly fish sauce predominantly found in ancient Roman cooking. Thus olive oil & Garum signify consumption by foreigners resident in Muziris and Kaveri Poompattanam. This as you can figure out implies the presence of Yavana colonies in these two locations.

So now having answered the question in a somewhat satisfactory fashion, I thought I would share a bit more of a complex discovery at Muziris and introduce you to a fascinating document called the Muziris Papyrus. Even though fairly recent (1985) in terms of discovery, it added a strong base to ancient international and trade laws in particular and has been studied at length by economists, lawyers as well as historians. The outcomes from the former is pretty dense, to say the least. But first let us start with a very quick summary on Muziris and the various discoveries over the last decade.

Rajappan. I do not know him, nor does anybody else I know. I do know however that he consented to have his land in the Paravur area dug up. And when that happened, around his house Krishna Nivas, they unearthed confirmation and sufficient archeological information finally enabling the announcement by Dr Shajan of the rediscovery of Muziris at Pattanam. There are still plenty of places to dig, but Kerala as you may know is densely populated, so the idea of relocating people for the purpose of archeology needs real hard sell and lots of monetary infusions. And so, thus far only about two hectares have been dug up.

More details can be found on this attached article and this.

When the trade with Muziris started is not known, however a document discovered recently, the Muziris Papyrus in 1985, takes us back to the 2nd century, by which time it seems to have been well established. During the Ptolemaic Roman period (third century B.C. to sixth century A.D), Berenike for example served as a key transit port between ancient Egypt and Rome on one side and the Red Sea-Indian Ocean regions on the other. Exotic goods from Rome and Egypt flowed into Berenike along the same desert road before being loaded into large ships bound for the Indian Ocean as I have explained in the past. According to most accounts, one of the major centers in India that ships from Berenike travelled to, along with the monsoon winds, was the emporium of Muziris, on the Malabar Coast. The presence of much teak in the finds at the red sea coasts also suggested that many of the ships were built in India, one of the indications of a major Indian role in the trade. But Dr. Casson, a specialist in ancient maritime history, says it was also possible that the teak timber was shipped to Berenike and turned into vessels there. Written records refer to ships in the India trade being among the largest of the time. That means, Dr. Casson says, that they could have been as long as 180 feet and capable of carrying upto 1,000 tons of cargo. Such ships had stout hulls and caught the wind with a huge square sail on a stubby mainmast.

The Roman ships with their square sail was not quite appropriate for sea travel with the winds, but it is more likely that the ships used were of Arabic Indian design as concluded by scholars. Even though the Muziris area was infested by pirates according to Pliny, and the need for transshipment to smaller boats, it figures to have recived more prominence than other like Nelcynda. One major spice the Romans sought via Muziris was Gangetic nard, spikenard or Jatamansi, after the popular Pepper. What the people in Malabar & Tamil regions needed was ( after the wine) the gold, which they never used as currency (the coins were mostly partly split making them non legal tender in S India) but possibly melted the coins and made ornaments.

What then brings us back to the Muziris papyrus ( also known as the Vienna Papyrus as it is kept in Vienna) ? It is the mention of a loan agreement made in Muziris. Now did Muziris therefore have a Roman settlement? Evidence points to that in two ways, one by a statement in the Periplus “enough grain for those concerned with shipping, because merchants do not have use for it’. The merchants are thus rice eaters, the Indians. Those concerned with shipping are the Yavana trader’s resident at Muziris. To this, one must also connect up the evidence of wine, olive oil and garum jars found at Arikumedu which date to the 3rd Century AD.

Of inestimable value for a study of the organization of trade are the Muziris papyrus and the archives of Nicanor. The Nicanor archives provide detailed information on the taxes levied on a variety of items transported along the desert roads from Myos Hormos and Berenice to Egypt. The papyrus confirms the distinction between those engaged in travel to the orient and local merchants.

The creditor lived in Alexandria in the 2nd century, the papyrus was sold by a collector in Egypt in 1980, and the loan agreement was drawn in Muziris and the papyrus is now housed in a Museum in Vienna. Two merchants documented their contract in the said document, listing the items, the costs and the people who owe and are owed money. Customs duties are listed, so also all the links in the chain such as the camel driver and how much he should be paid. I t mentions many people, signifying that this was not a financiers copy but by the trader himself. Interestingly the creditor had the first right of purchase which may possibly have been the first intention. The text also estimate steh value of the goods after a 25% tax has been deducted, but this amount itself is staggering, one shipload worth some 7 million Drachmas or sestertia (A solider was paid 100 drachmas maximum a month or around 800 per annum). The tax due at Alexandria was paid as goods, so the state itself did not get the money immediately. Possibly the trader had only to pass on a credit of the 25% tetarte (tax) and not the goods itself as moving the sates portion of the goods across the Coptos desert was not the traders responsibility. Considering the immense value it was carefully tracked from point to point. The Nard, the cloth and the ivory were the most valuable items in the holds. Camels and donkey owners handling these valuable items minted money from this trade billing the Roman government and were possibly escorted by military compared to the usual caravans. Towns along the Coptos desert charged tolls, and it is seen that the toll was dependent on the financial strength of the payer, thus variable.

No considering that Strabo talked of an average 120 ships going to Muziris every year, and multiplying the figure of 7million drachmas with the ships, you can imagine how much money flowed into Muziris and Malabar. This was how much goods of luxury were worth in those times. The question of if individuals had these kinds of fortunes or if a group worked together is not clear. However it is clear that the cost of failure meant death, so big were the amounts. Imagine a ship wreck or piracy, not thoughts meant for the faint hearted as eminent writer Sidebottom mentions in his book.

The first and second pages of this contract letter are lost so we are unable to know the name of the merchants who were engaged in business and the exact transactions at Muziris. In 1985 H. Harrauer and P. Sijpesteijn published the contents of this papyrus

It reads as follows (for complete paper check this link)

... of your other agents and managers. And I will weigh and give to your cameleer another twenty talents for loading up for the road inland to Koptos, and I will convey [sc. the goods] inland through the desert under guard and under security to the public warehouse for receiving revenues at Koptos, and I will place [them] under your ownership and seal, or of your agents or whoever of them is present, until loading [them] aboard at the river, and I will load [them] aboard at the required time on the river on a boat that is sound, and I will convey [them] downstream to the warehouse that receives the duty of one-fourth at Alexandria and I will similarly place [them] under your ownership and seal or of your agents, assuming all expenditures for the future from now to the payment of one-fourth-the charges for the conveyance through the desert and the charges of the boatmen and for my part of the other expenses.

With regard to there being- if, on the occurrence of the date for repayment specified in the loan agreements at Muziris, I do not then rightfully pay off the aforementioned loan in my name-there then being to you or your agents or managers the choice and full power, at your discretion, to carry out an execution without due notification or summons, you will possess and own the aforementioned security and pay the duty of one-fourth, and the remaining three-fourths you will transfer to where you wish and sell, re-hypothecate, cede to another party, as you may wish, and you will take measures for the items pledged as security in whatever way you wish, sell them for your own account at the then prevailing market price, and deduct and include in the reckoning whatever expenses occur on account of the aforementioned loan, with complete faith for such expenditures being extended to you and your agents or managers and there being no legal action against us [in this regard] in any way. With respect to [your] investment, any shortfall or overage [se. as a result of the disposal of the security] is for my account, the debtor and mortgager...

According to the Historian Thur, the contract between ego and tu was drawn up in Alexandria in two separate documents; one that spelled out the maritime loan and another that spelled out the security involved what the papyrus contains is a portion of the latter, the document that dealt with the security.

As Casson concludes - One of the great contributions of the papyrus is the concrete evidence it furnishes of the huge amounts of money that the trade with India required. The six parcels of the shipment recorded on the verso had a value of just short of 1155 talents almost as much as it cost to build the aqueduct at Alexandria The parcel of ivory and the parcel of fabric together weighed 92 talents and were worth 528,775 drachmas. A Roman merchantman of just ordinary size had a capacity of 340 tons; it was capable of carrying over 11,000 talents of such merchandise. And the weather conditions on the route to India were such as to require the use of vessels of at least this size. Loaded with cargoes of the likes of that recorded in this papyrus, they were veritable treasure ships.

With the listed part of that ships goods (only a part load) pegged at 131 talents, one could buy 2500 acres of finest farmland in Egypt and if there were 150 such ships every year, what would have that trade been worth? Immense, to say the least. The historian Pliny, who died in 79 A.D., has left us a contemporary account of these early voyages. "It will not be amiss," he says in his Natural History, "to set forth the whole of the route from Egypt, which has been stated to us of late, upon information on which reliance may be placed and is here published for the first time. The subject is one well worthy of our notice, seeing that in no year does India drain our empire of less than five hundred and fifty millions of sesterces [many many million dollars], giving back her own wares in exchange, which are sold among us at fully one hundred times their cost price.

Strangely the Malayali’s acquired taste of fancy Italian wine seems to have been eroded from the genetic code, to be replaced by the stuff from Scotland.

Note: this is only a brief introduction. I have deliberately not got into the depths of the analysis of the complex subject of trade for fear that this would then turn out into a long & boring paper.

References

New Light on Maritime Loans: P. Vindob G 40822 – L casson

Ships and the development of maritime technology on the Indian Ocean- Ruth Barnes, David Parkin

Periplus Maris Erythraei

The Natural history of Pliny

Rome's eastern trade: international commerce and imperial policy, 31 BC-AD 305 -Gary Keith Young

The monetary systems of the Greeks and Romans -William Vernon Harris

The Red Land: The Illustrated Archaeology of Egypt's Eastern Desert - Steven E. Sidebotham, Martin Hense, Hendrikje M. Nouwens

At empire's edge: exploring Rome's Egyptian frontier - By Robert B. Jackson

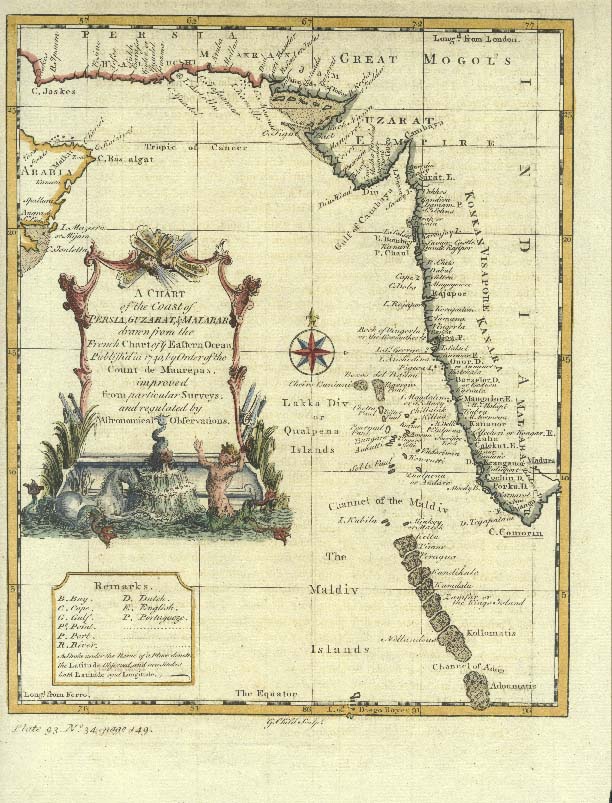

Pic courtesy - Trade map pic – Archeology news