Kamalludin Abudur Razzak (1413-1482), son of Jalaludin Ishak of Samarkhand was a man used to fine court life, but proved to be a bad traveler and not much of an emissary. His travelogue, promised to be filled with minutest detail, is an interesting book, strewn with poetic verses, which I suppose Razaaq believed were objects of wisdom that would provide guidance to the future reader.

Born 8 years after the death of Timor in Heart, he was the son of the widely traveled Qazi, of Samarkhand, and entered court life in 1437. Here he worked for various sultans of Khurasan such as Timor’s son the great Emperor Mirza Shahrukh. Apparently by late 1430, an invitation was accorded by the Zamorin of Calicut to Emperor Sharukh for an emissary to visit Malabar in order to improve commerce.

Note here in perspective that a century earlier, Ibn Batuta had visited Calicut and certified it as safe haven for merchants.

The choice of emissary befell the young Razzak who had been in the court’s employ for four years. The travel to the southerly parts of Hindustan proved to be no fun for the reluctant emissary who would probably have expected lavish receptions and plenty of gifts befitting an emissary of his stature. During the trip, he was frequently ill and complained bitterly of having been sent into these dark lands. Sanjay Subramaniam in his book listed under references, opines that the desire of Shahrukh to create a larger web of semi formal and suzerain relations going beyond the domains of Khorasan was the reason for the deputation of an emissary. It was not as many others said, and Abdur Razzaq based his trip on the premise that the Zamorin might convert to Islam if an appropriate ambassador was sent to Calicut by the great Emperor.

And thus Abdur Razak ibn Ishaq Samarkhandi started out on a journey that lasted three years between January 1442 to January 1445. I will take it up from his arrival in Calicut.

Quoting RH Major’s translations - The port at which he arrives is Calicut, where he speaks in terms of commendation of the honesty of the people, and the facilities of commerce. He does not, however, equally admire the persons of the natives, who seem to him to resemble devils rather than men. These devils were all black and naked, having only a piece of cloth tied round their middle, and holding in one hand a shining javelin, and in the other a buckler of bullock's hide. On being presented to the Sameri or King, whom he found, in a similar state of nudity, in a hall adorned with paintings, and surrounded by two or three thousand attendants, he delivered his presents, which consisted of a horse richly caparisoned, an embroidered pelisse, and a cap of ceremony. These did not seem to excite any warm admiration from the prince, and it is not impossible that, as the ambassador looked with considerable dislike on the people in spite of his commendations of their worthiness of conduct, his own manner may not have been remarkable for amiability. His stay at Calicut he describes as extremely painful, and in the midst of his trouble he has a vision, in which he sees his sovereign Shah Rukh, who assures him of deliverance. On the very next day, a message arrives from the King of Vijayanagar, with a request that the Mohammedan ambassador might be permitted to repair to his court. The request of so powerful a prince was not refused, and Abd-er-Razzak left Calicut with feelings of great delight.

At the beginning of November that year he arrived at Calicut after an 18 day voyage from Homrouz, where he had resided till the beginning of April 1443. Abul Razzaq now takes up the event in his own words

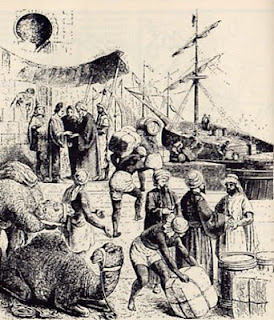

Calicut is a perfectly secure harbour, which, like that of Ormuz, brings together merchants from every city and from every country; in it are to be found abundance of precious articles brought thither from maritime countries, and especially from Abyssinia, Zirbad, and Zanguebar ; from time to time ships arrive there from the shores of the House of God and other parts of the Hedjaz, and abide at will, for a greater or longer space, in this harbour ; the town is inhabited by Infidels, and situated on a hostile shore. It contains a considerable number of Mussulmauns, who are constant residents, and have built two mosques, in which they meet every Friday to offer up prayer. They have one Kadi, a priest, and for the most part they belong to the sect of Schafei. Security and justice are so firmly established in this city, that the most wealthy merchants bring thither from maritime countries considerable cargoes, which they unload, and unhesitatingly send into the markets and the bazaars, without thinking in the meantime of any necessity of checking the account or of keeping watch over the goods. The officers of the custom-house take upon themselves the charge of looking after the merchandise, over which they keep watch day and night. When a sale is effected, they levy a duty on the goods of one fortieth part; if they are not sold, they make no charge on them whatsoever.

Calicut is a perfectly secure harbour, which, like that of Ormuz, brings together merchants from every city and from every country; in it are to be found abundance of precious articles brought thither from maritime countries, and especially from Abyssinia, Zirbad, and Zanguebar ; from time to time ships arrive there from the shores of the House of God and other parts of the Hedjaz, and abide at will, for a greater or longer space, in this harbour ; the town is inhabited by Infidels, and situated on a hostile shore. It contains a considerable number of Mussulmauns, who are constant residents, and have built two mosques, in which they meet every Friday to offer up prayer. They have one Kadi, a priest, and for the most part they belong to the sect of Schafei. Security and justice are so firmly established in this city, that the most wealthy merchants bring thither from maritime countries considerable cargoes, which they unload, and unhesitatingly send into the markets and the bazaars, without thinking in the meantime of any necessity of checking the account or of keeping watch over the goods. The officers of the custom-house take upon themselves the charge of looking after the merchandise, over which they keep watch day and night. When a sale is effected, they levy a duty on the goods of one fortieth part; if they are not sold, they make no charge on them whatsoever. In other ports a strange practice is adopted. When a vessel sets sail for a certain point, and suddenly is driven by a decree of Divine Providence into another roadstead, the inhabitants, under the pretext that the wind has driven it there, plunder the ship. But at Calicut, every ship, whatever place it may come from, or wherever it may be bound, when it puts into this port is treated like other vessels, and has no trouble of any kind to put up with.

Razzaq then details the gifts that have been sent to the Zamorin. Major as you saw felt that it was too cheap coming from a great emperor like Shahrukh. Now you can imagine why the Zamorin was furious with Vasco De Gama for the miniscule gifts they had brought from Portugual.

His majesty, the happy Khakan, had sent as a present for the prince of Calicut, some horses, some pelisses, some robes of cloth of gold, and some caps, similar to those distributed at the time of the Nawroz; (New year day in Persia) and the motive which had induced him to do so was as follows.

Some ambassadors deputed by this monarch, returning from Bengal in company with ambassadors of the latter country, having been obliged to put into Calicut, the description which they gave of the greatness and power of the Khakan reached the ears of the sovereign of that city. He learned from authentic testimony, that the kings of all the habitable globe, of the East as well as of the West, of the land and of the sea, had sent rival ambassadors and messages, showing that they regarded the august court of that monarch as the Kiblah, to which they should pay their homage, — as the Kabah, the object to which they should direct their aspirations.

Then Razzaq mentions about the power and influence of the Emperor Sharukh and his involvement of the emperor in ensuring that the King of Bengal and Jounpur did not go to war. It appears that the Zamorin had heard about this and so wanted to pay obeisance to the Emperor Shahrukh (A bit fanciful here, but let us leave it as such)

Razzaq states - As soon as the sovereign of Calicut was informed of these occurrences, he prepared some presents, consisting of objects of value of different kinds, and sent an ambassador charged with a despatch, in which he said : " In this port, on every Friday and every solemn feast day, the Khotbah is celebrated, according to the prescribed rule of Islamism. With your majesty's permission, these prayers shall be adorned and honoured by the addition of your name and of your illustrious titles.

These deputies, setting out in company with the ambassadors from Bengal, reached the noble court of the emperor, and the Emirs laid before that monarch the letter and the presents by which it was accompanied. The messenger was a Mussulmaun, distinguished for his eloquence ; in the course of his address he said to the prince, " If your majesty will be pleased to favour my master, by despatching an ambassador sent especially to him, and who, in literal pursuance of the precept expressed in that verse, ' By thy wisdom and by thy good counsels engage men to enter on the ways of thy Lord, shall invite that prince to embrace the religion of Islamism, and draw from his beclouded heart the bolt of darkness and error, and cause the flame of the light of faith, and the brightness of the sun of knowledge to shine into the window of his heart, it will be, beyond all doubt, a perfectly righteous and meritorious deed."

The emperor acceded to this request, and gave instructions to the Emirs that the ambassador should make his preparations for setting out on his journey. The choice fell upon the humble author of this work. Certain individuals, however, hazarded their denunciations against his success, imagining in their own minds that it was likely he would never return from so long a voyage. He arrived, nevertheless, in good health after three years of absence, and by that time his calumniators were no longer in the land of the living.

We also know that Razzaq was used to high life and proved to be a terrible racist. Here he continues thus..

As soon as I landed at Calicut I saw beings such as my imagination had never depicted the like of. Extraordinary beings, who are neither men nor devils, At sight of whom the mind takes alarm; If I were to see such in my dreams , My heart would be in a tremble for many years.

I assume he saw a Velichappad , the oracle, divine dancer or light revealer

I have had love passages with a beauty, whose face was like the moon; but I could never fall in love with a negress (ill proportioned black thing in certain other translations).

Describing the indigenous population, probably not meeting or seeing not the fairer people, he states

The blacks of this country have the body nearly naked; they wear only bandages round the middle, called lankoutahy which descend from the navel to above the knee. In one hand they hold an Indian poignard (Actually written as Katarah or dagger), which has the brilliance of a drop of water, and in the other a buckler of ox-hide (Leather shield), which might be taken for a piece of mist. This costume is common to the king and to the beggar. As to the Mussulmauns, they dress themselves in magnificent apparel after the manner of the Arabs, and manifest luxury in every particular.

Here I assume he means the Pardesi Arabs, not the Moplah’s

After I had had an opportunity of seeing a considerable number of Mussulmauns and Infidels, I had a comfortable lodging assigned to me, and after the lapse of three days was conducted to an audience with the king. I saw a man with his body naked, like the rest of the Hindus. The sovereign of this city bears the title of Sameri. When he dies it is his sister's son who succeeds him, and his inheritance does not belong to his son, or his brother, or any other of his relations. No one reaches the throne by means of the strong hand.

The Infidels are divided into a great number of classes, such as the Brahmins, the Djoghis, and others. Although they are all agreed upon the fundamental principles of polytheism and idolatry, each sect has its peculiar customs.

Amongst them there is a class of men, with whom it is the practice for one woman to have a great number of husbands, each of whom undertakes a special duty and fulfils it. The hours of the day and of the night are divided between them; each of them for a certain period takes up his abode in the house, and while he remains there no other is allowed to enter. The Sameri belongs to this sect.

When I obtained my audience of this prince, the hall was filled with two or three thousand Hindus, who wore the costume above described; the principal personages amongst the Mussulmauns were also present. After they had made me take a seat, the letter of his majesty, the happy Khakan, was read, and they caused to pass in procession before the throne, the horse, the pelisse, the garment of cloth of gold, and the cap to be worn at the ceremony of Nauruz. The Sameri showed me but little consideration. On leaving the audience I returned to my house. Several individuals, who brought with them a certain number of horses, and all sorts of things beside, had been shipped on board another vessel by order of the king of Ormuz ; but being captured on the road by some cruel pirates, they were plundered of all their wealth, and narrowly escaped with their lives. Meeting them at Calicut, we had the honour to see some distinguished friends.

By no means did Razzq enjoy his stay at Calicut, he explains....

From the close of the month of the second Djoumada [beginning of November 1442], to the first days of Zou'lhidjah [middle of April 1443], I remained in this disagreeable place, where everything became a source of trouble and weariness. During this period, on a certain night of profound darkness and unusual length, in which sleep, like an imperious tyrant, had imprisoned my senses and closed the door of my eyelids, after every sort of disquietude, I was at length asleep upon my bed of rest, and in a dream I saw his majesty, the happy Khakan, who came towards me with all the pomp of sovereignty, and when he came up to me said : "Afflict thyself no longer." The following morning, at the hour of prayer, this dream recurred to my mind and filled me with joy. Although, in general, dreams are but the simple wanderings of the imagination, which are seldom realized in our waking hours, yet it docs sometimes occur that the facts which arc shown in sleep arc afterwards accomplished ; and such dreams have been regarded by the most distinguished men as intimations from God. Every one has heard of the dream of Joseph, and that of the minister of Egypt.

As you read between the lines, you start to understand the reasons, which have also been explained in detail in Sanjay Subramaniam’s book. The conversion of the Zamorin was pretty much a chimeara, an illusion, an impossibility. Soon the noble king is reduced to a ‘Wali’ a keeper in Razaak’s travelogue.

A very interesting observation here, and we hear about the relationship between the Vijayanagara kings and the Zamorin, though one must take razaak's words with a pinch of salt.

The inhabitants of Calicut are adventurous sailors: they are known by the name of Tchini-betchegan (son of the Chinese), and pirates do not dare to attack the vessels of Calicut. In this harbour one may find everything that can be desired. One thing alone is forbidden, namely, to kill a cow, or to eat its flesh: whosoever should be discovered slaughtering or eating one of these animals, would be immediately punished with death. So respected is the cow in these parts, that the inhabitants take its dung when dry and rub their foreheads with it. The humble author of this narrative having received his audience of dismissal, departed from Calicut by sea. After having passed the port of Bendinaneh, situated on the coast of Malibar, we reached the port of Mangalor, which forms the frontier of the kingdom of Bidjanagar.

But why should Sons of the Chinese be feared? Did they all leave after the tiff with the Zamorin, as we discussed in a previous blog? Were they in anyway related to the marakkars?Food for thought.

The place Bandinaneh is probably Balipatanam in Cannanore.

Abdur Razzaq also wrote about betel chewing which he witnessed everywhere, thus - "The virility of the king is attributed to his habit of chewing the betel leaf, as it lightens up the countenance and excites an intoxication like that caused by wine. It relieves hunger, stimulates the organs of digestion, disinfect the breath and strengthen the teeth. It is impossible to describe and delicacy forbids me to expatiate on its invigorating and aphrodisiac qualities."

By the time Abdur Razzaq returned home, his master Shah Rukh was dead and Abu Said Mirza was fighting for the throne. Quickly he recognized the new Sultan and was accepted after which he settled down to write his memoirs. He died in 1482. His memoirs of Calicut went on to set a great perspective before the arrival of the Portuguese.

References

Indo-Persian travels in the age of discoveries, 1400-1800 - Muzaffar Alam, Sanjay Subrahmanyam

Album prefaces and other documents on the history of calligraphers and painters - Wheeler McIntosh Thackston

India in the 15th Century –RH Major