Vadakan pattukal came to light in the 16th century, but there were vernacular poets even before that and the first such documented poetry is the story of Nilakesi in ‘The Payyanur paattu’. Dr Herman Gundert unearthed it during his days in Telicherry in the 19th century and transported some of what he obtained to Germany. Since then, it has been much talked about. This is not an in-depth study and I am happy to say that there is plenty of material out there and many experts have conducted solid studies on the subject. So consider this just an introduction to the uninitiated with a request to read the other available material, if history interests you.

When you unearth a bit of colloquial poetry like the Payyanur Paattu which tells a story, you would first concentrate on the story. The story in this case is only the medium, expressing human relationships and emotion, striking the chord with the public. But as a text from even earlier times, it hides in between the jumbled words, a good amount of history, especially relating to trade and cultural activities of a period. So when this appeared, the rich treasure trove was dissected by the learned and the wisdom gleaned from it is rather illuminating, so to speak. And that is why it is much heralded in recent times.

Payyannur (actually termed as Pazhayannur in the poetry) incidentally is the Northern most district of the Chirakkal taluk and finds mention from Parusurama’s times as the seat of the Payyannur Grammakkar. These people were the Brahmins specially favored by ‘Parasurama’ and had even practiced ‘matrilineal maraumakkattayam’ and not the Vedic prescribed Makkattayam inheritance system which Namboothiri’s later followed.

The Payyanur Paattu is a ballad dedicated to a local goddess and written around the 13th or 14th century in Malayalam by an unknown writer belonging to the trading Chettiar community. While almost all textual work in India is attributed to the scholarly Bhrahmin class (for only they were allowed study of scriptures & Sanskrit), this was done by the merchant sect or Chettys. Interestingly, while many relied on the word of mouth, Chettys had to write out their accounts & contracts, so were used to writing things. The document when first discovered by Gundert was incomplete, only some 104 verses or 448 lines in all were found, and is still largely incomplete. However the story line has been augmented by other contemporary poetry to come to an acceptable conclusion.

The Payyanur Paattu is a ballad dedicated to a local goddess and written around the 13th or 14th century in Malayalam by an unknown writer belonging to the trading Chettiar community. While almost all textual work in India is attributed to the scholarly Bhrahmin class (for only they were allowed study of scriptures & Sanskrit), this was done by the merchant sect or Chettys. Interestingly, while many relied on the word of mouth, Chettys had to write out their accounts & contracts, so were used to writing things. The document when first discovered by Gundert was incomplete, only some 104 verses or 448 lines in all were found, and is still largely incomplete. However the story line has been augmented by other contemporary poetry to come to an acceptable conclusion.

The original text runs as follows and then stops abruptly, for that was all Dr Gundert could get out of the manuscript he received and exemplified as “certainly the oldest specimen on Malayalam composition which I have seen”. He adds “the language is rich and bold, evidently of a time when the infusions from Sanskrit had not reduced the energy of the tongue, by cramping it with hosts of unmeaningful particles”. Gundert and many others studied this one and only fragment without corroboration of text or matter from other sources. Due to this reason, understanding of some of the words were difficult not only to Dr Gundert, but even today’s Malayalam experts. But naturally, for this was heavy colloquial poetry with a large dose of trade related usages & words, that are still being deciphered.

For now, I will condense the story a bit…

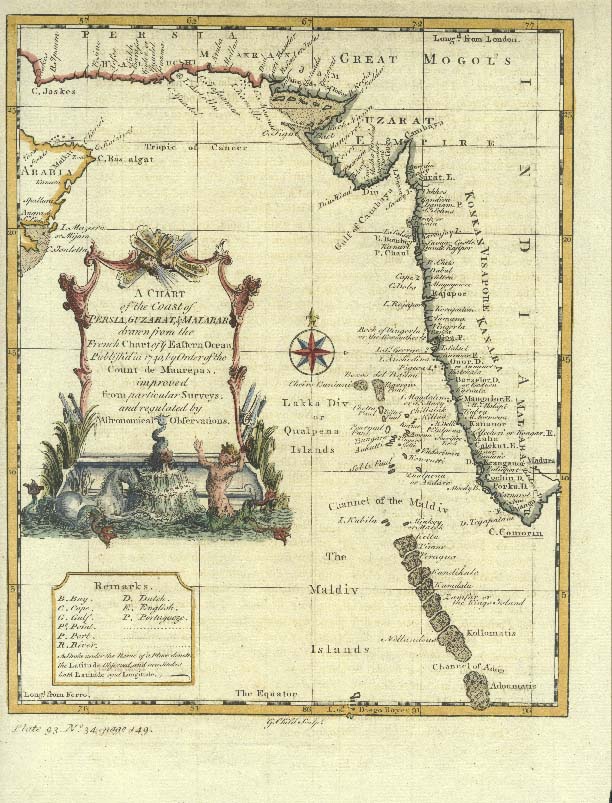

The son grew up and the father taught his son everything about trade and ship building. The father gave him a new ship for trading and the son plans to man it with Vapuravas, Pandyas, Jonakas, Chuliyas,Pappavas and a Yavana. The ship is loaded, launched and it sets out to Poompattana near Ezhimala, and then goes to the Maladives, to Puvenkapatana, then up the Kaveri River to another sea and finally the shores of the Gold Mountains. Here the trader and his team barter their goods for a heap of gold and return to Kachilpatanam and dismisses his mariners with their share of gold and profits.

This poem is very important for historians and anthropologist for a few reasons. One, it was the first documented poem and secondly it was passed on by tradition in the vernacular. The story was completed only from the Theyyattam songs of the area, as narrated by the washer man or ‘mannan’ caste. How did the story go from the Chetty guilds to the Mannan caste? Also it was the first document that identified the merchant guilds existing between the 9th and 13th century. Later studies established the details of the said guilds, more on that and the Ayyavole guild in a follow up blog.

Then again, this is the first documentary evidence of Changathams and Chavers in Malabar. They are alluded to in the poem as mercenaries and support for the trading caravans (it says – Chavalarepole Niyakkalepovum, Changatham venam Perikkayipol).

In the passages where the father teaches the son, there are mentions of book keeping methods, as well as understanding purity of metals. Good qualities that a trader should possess are meticulously explained and also the fact that trade comprised rice from other Eastern areas (as it was ferried by ship) is clear from some paragraphs (showing a scarcity in Malabar). As we know now, Valluvanad & Kuttanad were the areas where rice was eventually cultivated.

It was also one of the earliest mentions of chess or Chaturangam being played in Kerala. It is known that Namboothiris used to play it a lot, even demarcating temple grounds with huge pieces and squares to signify the board, but this is documented proof of others playing it and describing the pieces. All the chess pieces are named: King (Mannava), Horse (Kutira), Elephant (Varana), Chariot (Ther), Footmen (Natakkum Chevakan) and Minister (Mantri).

Anyway, the wise Gundert Sayyip took his collection including this fragmentary ballad and stored it in the Tuebingen Library where it rested peacefully and safely. I shudder to think of the consequences had it been left at its place of origin, we would never have got richer with all this information & history. And it explains the special attachment of the woman of Malabar to her matrilineal family, where for example the husband comes second. It also hovers around the kind of confusion that Abraham Ben Yiju felt about Ashu’s relationship with her brothers.

Many years later the rest of the story was obtained as part of a washer mans’ exorcism ballad. These mannan’s performed ‘teyyattam’ for the merchant community. So the Paattu as we know today is a hybrid of the manuscript and the vernacular ballad, a hybrid poem. The second poem is called Nilakesi Paattu where Nilakesi meets up with Nambusari and they have a contest of chess in which he gets defeated. Nilakesi then takes the story to the end, which is, as she avowed, his death. So to complete the story, the mother Nilakesi kills her son in revenge.

People had access to Gundert’s simplified version of the Payyannnur Paattu in the Madras journal of Literature & Science (XIII-II) April 1884, but not the original parchment until recently. It rested in the Tuebingen University and nobody had any real clue about this Malayalam script, i.e. till Dr Scaria Sachariah came along. But in passing Gundert Sayip concluded thus ‘I believe that the people of Anjuvannam and Manigramam here mentioned as belonging to yonder country can only mean Jews and Christians (or Manicheans) who for commerce’s sake also settled beyond the Perumal’s territories. It would be interesting to know which the other two classes are. In the meantime the existence of four trading communities in Kerala seem proved, and the ‘nalucheri’ of the first Syrian document receives some elucidation from this incidental allusion.’

For now, I will conclude. This as I mentioned, is only an introduction. Reading the books referred below will provide a history enthusiast great perspective and much information about culture, trade and relationships of that time…

Introducing the experts

Dr. Scaria Zachariah, professor of Malayalam, at the Sree Sankara

University of Sanskrit, Kalady, is an expert in 16th century Malayalam . P Antony was a student in the same university, and researching on Vadakkan Poattukal.

University of Sanskrit, Kalady, is an expert in 16th century Malayalam . P Antony was a student in the same university, and researching on Vadakkan Poattukal.Others who have written various essays on this subject are Prof Guptan Nair, Dr Leelavati, Mahakavi Ulloor, MGS Narayanan, Venugopalan Nambiar, K Balakrishnan, Dinesan, Sajitha, T Pavithran to name a few, these can be read in the Tapasam issue.

Dr Gundert – See my previous blog on The Sahib & Collector. An additional footnote about Dr Gundert - "There is something that many people do not know about Mr. Gundert. He actually began his work in Tamil Nadu as a private tutor to the son of a British missionary. He had stayed in Madras, then in Tirunelveli, all of which is recorded in his diary. Mr. Gundert was not a missionary, he was never ordained. He was always a teacher. In Chittoor, Andhra Pradesh, he had established 10 schools. Very few know that Mr. Gundert had written a Tamil-Greek, a Hebrew-Tamil dictionary and a Church History in Tamil. But this has been lost forever. He had given the manuscripts to possibly the mission press in Nagercoil in October 1838, but our efforts to dig this out has failed," informs Dr. Albrecht Frenz, his great great grand daughter

More details on this subject and related areas will follow

References

Payyannur Paattu – Paadavum Padanavum - Dr Scaria Zacharia, P Antony

Tapasam – Vol II, issue 2, July 2006 with many articles on PP