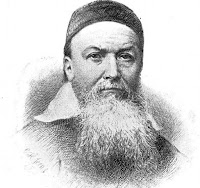

Rev Jacob Rama Varma

Posted by Labels: Cochin prince convert, Jacob Rama Varma, Malabar - English period 1900 -1950The converted prince

Today it may not look curious or alien, for many a person has moved across religions to find peace and solace in life, treading different paths to those they were used to or born into, some successful, whereas others reverted after a period of confusion. But in the 19th century, it was a rarity and when a person from the Cochin royal family did just that, it was much talked about. We get to read the details of Rama Varma’s life and times from the diaries of his contemporary Herman Gundert as well as some other musty sources, available at the Tubingen library.

In fact, it was a time when caste divisions and separations

were at its peak, and missionaries were doing their best to increase bragging

rights on conversion numbers. While conversions among lower classes and castes

were common, getting somebody to convert from the upper classes was a rarity

and for that reason, noteworthy. This was so considering that the Syrian

Christian community of Travancore, who predated the new Protestant and Roman

Catholic missionaries claimed superior descent from the Namboothiri community.

Three conversions are often mentioned in history texts, the first the Raja of

Tanur in the 16th century, the second being a Zamorin’s nephew who

also converted also in the early 16th century and the third being

the Cochin prince we are going to talk about.

In Cochin, it was a period witnessing a turbulent change,

after the ruling family had adopted Vaishnava Madhavism, embracing the Dviata

Vedanta. Madhavacharya who established the Udupi Mutt propagated a dualist

philosophy as against Adi Shankaracharya’s Advaita (Brahman and soul are one) which

in essence stated that Vishnu and human soul are two different entities.

In 1828, Veera Kerala Varma died and his brother Rama Varma

took the throne, but due to some animosity between the brothers, the deceased

kings family had to leave the palace and go to live at Vypin. The 14-year-old

boy trudged through various difficulties as we see till one Col Morrison

interjected and brought about a compromise between the two families.

Nevertheless, the young boy maintained an ascetic life, helping at the temple,

mastering the puranas and various hymns and stotras, secure in the belief that

his god, the Tripunithara Devan i.e., Vishnu Jaganath would take care of him. He

also believed firmly that if anybody did anything wrong, the Deva would punish all

such evil doers. This simplistic belief and the lack of knowledge of the cruel

ways of the world, would only give this young fella a lot of grief, as we shall

soon see!

As the story goes (this is all incidentally from the

firsthand account of the prince) an Embranthiri (Tulu brahmin priest) associated

to the Rama Varma palace, became the chief priest of the temple and before long

absconded after stealing the expensive gold ornaments worth some Rs 15,000,

never to be caught even after extensive investigation. The young Rama Varma

prayed for the thief to be caught and as you can imagine, nobody was

apprehended, leaving behind a befuddled youngster who concluded that temples,

idols and this particular god was a sham, unable even to catch a petty thief

who stole the god’s treasures. Adding insult to injury, another theft occurred,

and this time the idol itself was stolen by another priest, and nobody was

apprehended. The young mind was, as we read, shattered beyond belief and he

lost all faith in his bhagavan, and he stopped going to temples, though his

study of puranas continued unabated.

Having abandoned previously nurtured beliefs, the young

prince’s mind wandered and we read that he spent time studying taboo subjects

such as Kamasastra. Now the reader must realize that the society in Travancore,

Cochin and Malabar had already become terribly corrupted by caste beliefs and

strict norms on what is right and wrong, perhaps tainted also by Sankarasmriti

and the such and compounded by even narrower paths tread by the many

missionaries and their definitions of western morality. We can see from Rama Varma’s words that he

was terrified of getting excommunicated or being cast off from his society, and

it was only after getting ordained, which meant getting his thread ceremony (recall

that Varma’s belonged to the kshatriya caste and wore the punool (sacred

thread), unlike Nair’s) completed, that he breathed a sigh of relief for he was

now on his own. It appears he decided to follow a life of sin, though we do not

know what he was upto (perhaps experiencing the normal joys of flesh, albeit

illicitly per the norms of the day), other than this admission. This aspect

will become even more relevant in the next life of Rama Varma and will be

touched upon, later on.

There are mentions of his laying hands on a Bible gifted by

a ship’s captain to his brother and not quite understanding what it was all

about, and another about his young nieces’ untimely death which again raised

visions of hell, but the next important step was when the young man decided to

join the Mission school started by Rev Ridsdale, in Cochin around 1832. A

reader today would wonder if the boy had latent mental issues which were being

manipulated by these incidents, but remember that in those days, it was believed

that he was being punished for his evil deeds. Anyway, at the school, he found

himself heartily agreeing with the teacher Ridsdale about the vagaries of idol

worship and took to learning and understanding the nuances of the New Testament,

by heart.

Around this time, he is joined by a Konkani brahmin Ananthan

and together the boys get interested in the study of the Christian scripture.

We continue to see the fear of death and hell overpowering the prince at times.

The turning point came on a rainy day, when a boat which he is traveling on

nearly capsizes. The boy prays to his new savior, survives the ordeal and decides

to choose the path of Jesus Christ and get baptized. His personal cook conveyed

the decision to his mother, who calls the prince back home, to Tripunithara. At

this juncture, the boy develops a boil on his stomach which the local

physicians confirm is incurable. Prayers to Christ help and the boil is cured,

after which the boy hastens to Cochin, to get baptized. On 5th April

1835, Rama Varma is given the name Constantine and Ananthan his friend becomes

Yohannan. Their sacred threads or punools are broken and cast away and the boys

dine with the Europeans raising a hue and cry in Cochin and Tripunithara. Rama Varma’s

brother is furious and arrives with a dagger to stab him, but when they met,

the antagonism disappears. Their fond relationship apparently continued with

the elder brother always helping out Constantin Rama Varma with monetary gifts,

in times of need. At the kovilakom, Rama Varma is cast away from his Hindu

family, his death rites are conducted and is for all practical purposes,

forgotten.

Constantine’s travails as a newborn Christian are

interesting, though we see some gaps. We see that the young fella goes to

Madras in 1837 for further studies seeing that Ridsdale has little time to

educate him, being busy in many other important activities. He joins the Bishop

Corrie’s grammar school for English studies. It is here that he meets up with

the Syrian Catholic Maramanna Mathan or Mar Athanasius and some other famous

pastors. But on his return to Cochin, he is admonished for getting friendly

with the Syrian Catholics. Anyway, Mathan plans a trip to Antioch (now Antakya-Turkey)

and Rama Varma decides to tag along, desirous of visiting Jerusalem. They were

supposed to catch a ship from some west coast port, perhaps Goa but stop for a

while at the Christian missionary station in Belgaum, run by a Rev Joseph

Taylor. Taylor tells them to hang on until the monsoon is over and they wait,

but as the rainy season draws to a close, Varma is afflicted by a case of

severe conjunctivitis and cannot travel, so he remains at Belgaum and continues

as a tutor for Taylor’s children, teaching Tamil and the Bible’s content to

them, for the next 18 months. He also preaches to the locals in Kannada, during

his spare time. Sometime later, Taylor’s children go back to Britain and Varma is

asked to teach at the ‘Black School’.

Here is where the accounts start to differ. The sketches of

Indian Christians by Sathianandan written in 1896, which had been following Varma’s

own account, glosses over the reason for his departure from Belgaum, back to Malabar.

Varma in his account, states that he committed a grave sin (I can only guess

that it was something to do with an illicit sexual encounter, since Varma

mentions that he was doing it after 13 years) at Belgaum for which he is castigated

and decides to leave the Taylor mission. Taylor suggests that Varma contact

either Moegling at Mangalore or Samuel Hebich at Kannur, if he intended to stop

at those places.

He was cordially welcomed, but at once tested as to

whether he would endure humbling. Hebich from the first refused to know him by

what he called “the fatally royal name of Constantine,” calling him simply

Jacob. He writes, “it is unfortunate that so often a great fuss is made about

the conversion of people of such high caste; the poor fellows cannot stand it;

their heads get turned; and then they have to pass through a time of bitter

penitence.”

The reaction of the local Chirakkal Raja, was mixed. He had

gifted the mission some land, but on the condition that no cows were to be

slaughtered there. Gundert mentions that - He was a man of some experience

and education; but in his old age had found out the vanity of all his learning,

and had devoted himself exclusively to the worship of the thirty-five tutelary

deities of his house, with the most minute ceremonial. He had even shunned

intercourse with Europeans. He shuddered at hearing from his nephew, the second

Rajah before mentioned, that the English were actually printing the Vedas, of

which he had himself seen the first volume at the mission-house. This second

Rajah, however, welcomed into his neighborhood a well-educated man like Jacob,

and seldom allowed any of the objections urged by others, to keep him from

daily intercourse. This intercourse did not, however, win him any nearer to

Christ.

He then tells us about the Malayalam tuitions rendered by

Jacob to the two British soldiers Joseph Searle and George O’Brien. But his

formal work at the pulpit was not of such great quality and we see - From

the first he had to act as interpreter at Cherikal; he says it made him tremble

from head to foot, his heart beat, and his tongue failed him; so that Hebich

told him to go into the next room and recover himself. He sat there awhile,

weeping, and then commanded himself sufficiently to continue interpreting to

the end of the preaching. Afterwards, he also humbled himself, and confessed

his sins, though keeping back the blackest part of his guilt. He felt as one

intoxicated, unable fully to control his actions. Afterwards, when it came to

the preaching in Cannanore, he felt as though a fire burnt in his bones, as

though it were already hell-fire. Eventually it seems that Jacob confessed.

Gundert continues - His food was ready, so he sat down to

it, putting his hand into the dish of rice; but then he could bear himself no

longer; without even staying to wash his hands, he sprang in to the missionary,

exclaiming, "I am lost! I committed such and such sins when at Belgaum. I

resisted justice, and told lies in hypocrisy.” But no sooner had he thus made

open confession, than he found peace in the sense of forgiveness in Christ.

After the lapse of years, he can still joyfully look back upon that moment, as

to the birth of a fresh life in his soul!

In 1850 Hebich embarked on a preaching trip, accompanied by

Jacob, Joseph, O'Brien, Paul, and some of the boys. They sailed down the coast,

landing at Ponnani and continued to preach at Palghat and other places. Hebich adds

made some comments about his ward - The lads who were being trained for

mission-work under Jacob at Cherikal were not going on satisfactorily. Jacob

taught them faithfully enough; but he lacked the energy which would have

enabled him truly to educate the whole character, moral and intellectual. Anyway,

as the Europeans preached, Jacob translated and even endured stoning on certain

occasion.

Hebich narrates how on one of the "pelting days” (15th

of March, 1853), a stone rebounding from Joseph's umbrella cut open the

upper lip of a Mapilla who was standing behind him; another stone whistled past

Hebich's head, hit the tree under which he was standing, and glancing from it,

struck a Nayer in the forehead, so as to draw blood and make the whole head

swell. A fellow threw a cocoanut husk at Jacob; hitting him so hard in the

chest as almost to knock him off the low stone-wall on which he was standing.

Eventually we get to Jacob’s ordainment in 1851 - At the

last General Conference, Jacob Ramavurma had been examined and recommended for

ordination. After Jacob had given a sketch of his life, with sundry practical

applications, Hebich ordained him according to the formulary in use with the

Church in Wurtemberg; the witnesses uniting in the laying-on of hands, in token

of their desire to call down upon him needed blessings. The service was

concluded with prayer and singing, and then the missionaries welcomed their new

fellow-worker with a brotherly kiss.

The (Chirakkal) rajah sought to conceal the impression

made upon him, saying all religions came to much the same in the end. His

followers urged him to come away, and he excused himself, smiling the while,

that as it was the fourth day of the moon's age, he must hasten home, as it was

wrong for him to be abroad while the moon was so young. He pressed Jacob's hand

(some might recall that the Cochin and the Kolathunad Rajas are related),

congratulated him and expressed good wishes on a day so honorable to him, and

away he went, to wash off the contracted impurity in his tank, and (as

Gundert puts it) to hide himself in the dark recesses of his palace. To

Jacob was now assigned the oversight and pastoral care of the Cannanore

Christians, together with the Sunday catechizing and other services, even to

English preaching. But his main aim was directed to the five schools, his

attention to which was most beneficial.

Jacob had been so true and earnest in enforcing

scriptural teaching on the pupils of the English School, that they took a

violent dislike to him. They thought that they were there to gain secular

knowledge and not to be preached to. One of these pupils, however, sprung of a

respected Tiya family, on reflection, felt ashamed at this hatred. About the

same time, a young Nayar, of Cherikal, over whom Jacob had long yearned, was

impressed. These two lads both came to the mission-house on the 27th

of December, resolved to confess to Christ. Hebich joyfully welcomed them, and

cut off their caste-locks.

Interestingly, we come across one account where you can also

detect a good amount of racism prevalent between the Europeans (even Hebich and

Gundert) and the locals including Christian converts. Hebich mentions the

following in a sermon, while trying to win over more followers from the British

army men stationed there – “Be prepared to render an account of your stewardship!

Remember what a damnation it will be to us Europeans, if a Native, like Jacob,

should enter heaven before us. Amen!"

Gundert had also mentioned thus about Jacob Ramavarma whom

he had taught German in Chirakkal: "On 14th January 1854, assisted in the

examination of catechism pupils and found that they had made good progress in

German (My pupil, the catechist Jacob, perhaps knows more words and reads more

easily but quite a few Mangalore pupils are better-versed in the main words and

can build more solid sentences as a consequence). Jacob thus spoke many

tongues, Malayalam, Sanskrit, Kannada, Tamil, German, English, quite an

accomplished character, all in all!

And we now come to the end of Gundert’s account of Jacob - In

January, 1857, a dear young man of the Mullil family was taken ill with

small-pox. Rather unwisely Jacob was sent to visit him; not by Hebich, however,

who well knew the fear this tender-hearted man had of that terrible disease.

Jacob went, however, unhesitatingly, and faithfully acted as kind nurse, but he

took the infection. He at once said: “I shall not get over this sickness; but I

am ready to go or to stay, as shall please the Lord, and I rejoice in the hope

of a glorious eternity.” He fell asleep on the 11th of February 1857,

in the arms of his loving and faithful wife.

This was a great blow to Hebich and he writes: “I can

hardly make others understand what a treasure I have lost. For these last

fourteen years he has been as my mouth at Cannanore, at the heathen-festivals,

where he ever stood hard by my right hand, and in all the country round. Since

his ordination, I have noticed that dear Ramavurma was increasingly earnest and

zealous in his purposes. Praised be the Lord of all grace, for all that He has

done in and through my beloved Jacob. Amen.” Jacob's kindly figure was missed

on all hands.

Gundert adds - Small as he was in body, he was in many

respects a complement of Hebich's character. He softened and moderated; he

diffused joy: he brought regularity and method into the ordering of the Church;

and so, with all submissiveness, was most helpful to true progress. Another

friend wrote: “May God comfort the poor widow! for seldom were a couple more

tenderly attached; they were like a pair of turtle doves." All combined to

do him honor; many of the officers of the garrison even following him to the

cemetery.

Gundert acknowledged the Chirakkal Raja later as his friend:

"Jacob Ramavarma followed my old friend, the Chirakkal Raja in his

mortal illness of small-pox. The Raja had witnessed Jacob's ordination in the

church. He had distributed sugared water in the streets before his death."

Jacob Ramavarma and the Raja were close friends: "Unfortunately, small-pox

has reached the Chirakkal girls' institute. Even the old and friendly Chirakkal

Raja has died of it and also his friend Ramavarma at whose ordination he had

followed in procession, clad in an ornate red-and-gold silk garment, but sadly

without having come to the faith."

Rev Hebric’s letter to Gundert gives slightly different

details, wrongly mentioning the affliction as measles instead of smallpox - “After

you departed from Kannur, Ayyan Ramavarman got infected with measles and

subsequently, the master passed away. On 2nd February, I went to

Kannur and saw him in a pitiable condition with red spots all over his body. I

could not even see him personally because Hebich sahib had warned against it.

However, some people from Anjarakkandi and his own wife were with him. Those

who met Ramavarman realized the fact that the disease was getting worse. Doctor

advised him to apply boiled coconut oil on his body. However, his condition got

worse day by day. Ayyan (master, a priest; a word of respect) even lost his

consciousness occasionally. When sahib met him once, he expressed his happiness

and relief in meeting him.

Ramavarma’s Tamil wife who was named Rahel, later married the catechist Timotheous (Timothy) Parayil and passed away circa 1869.

So, friends, that was the story of

a man from the Cochin royal family who converted and lived his life as a catechist

and priest, in those dark days when caste and religious strictures were overt,

when much time was spent on discourses and studies on which religion or caste

was more superior to the other. It was also a period when western religions

tried their best to add converts to their fold. But there was a silver lining

to this turbulent period, education got normalized, schools, convents and

colleges came about and lower castes and classes were exposed to education, the

letters and school. The Malayalam language, its script and grammar got

formalized to what we see today and the institutions of printing, publishing flourished.

Newspapers and books became popular. The Basel Mission was in many ways

responsible for much of this.

The life of Samuel Hebich: by two of his fellow-labourers- Col JG Halliday (Hermann Gundert in German)

Autobiography of Jacob Ramavarman, the Native Missionary – (Trans) Rajesh V Nair

Sketches of Indian Christians – Sathiananthan

Samuel Hebich of India – Rev George Thomssen

Dr Herman Gundert and the Malayalam Language – Dr Albrecht Frenz, Dr Scaria Zacharia

Keralopakari – Jan-May 1879, Tubingen library archives

Basel Mission Obituary, English Autobiography Br Jakob Ramavarma

Umare Charare - The Zamorin’s nephew

4 comments:

Manmadhan sir,

Great story, as always. Really enjoyed reading this.

Bernard

Thanks Bernard..

glad you liked it..

Where is Rama varma buried ? Any tomb exists?

I have no idea George,

May have been cremated due to the disease. If not the grave must be in the Basel Mission burial grounds

Post a Comment