The Spanish connections to India – Manila & Mangalore

History is full of surprises. It is stories like these that make the subject fascinating, especially since some are hidden deep in dusty books, prompting people like me to seek them out. This story features a remarkable Jewish merchant named Goldsmith and how he managed to broker a deal between the Spanish crown and the Mysore Sultan, Hyder Ali. It was an elaborate scheme involving a baby elephant, one that could have caused chaos in the already tense relationship between the British and the Mysore Kingdom, with the potential to alter the course of history. Let's go to the region and find out what happened.

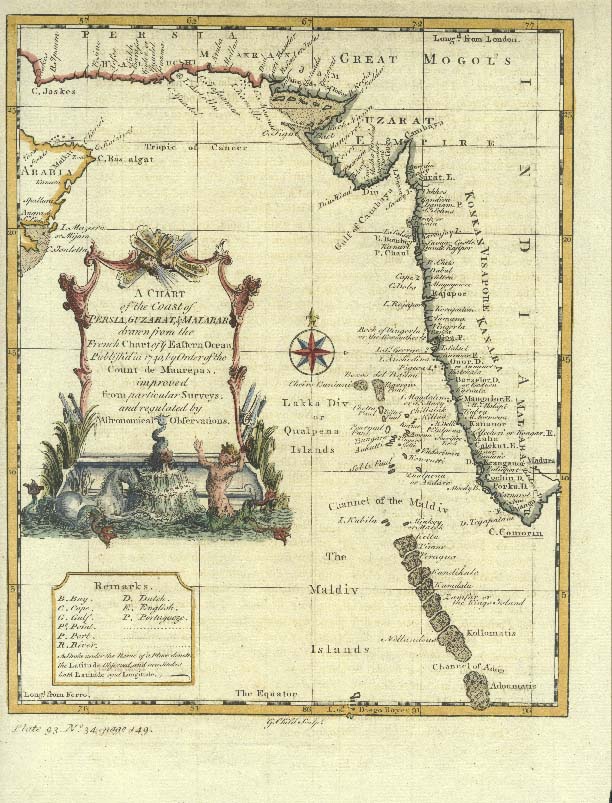

There were hardly any trade links between Spain and India

during medieval times, except for occasional illicit activities between the

Spanish-controlled Philippines and Malabar during the Portuguese and Dutch

eras, and, of course, some slave trading during the Dutch interregnum. However,

the Spanish monarchs desired much from the Indies, including exotic animals and

spices.

But first, let us meet the main protagonist of the story: a

Jewish merchant from Hamburg named Isaac Berend Goldschmidt (also known as Goldsmith).

A very clever individual, he managed to survive and navigate in extremely tough

conditions. He was one among the Jewish coterie we have encountered so far,

such as Ezechiel Rahabi of Cochin and Isaac Surgun of Calicut, who were his

contemporaries. According to his own account, he traveled to Malabar in 1756 as

a merchant and later moved to England. After a short stay in London, he

returned to India in 1764. He settled at Fort St. George, in 'Maduwara' (which,

according to his notes, seems to have been the original name of Madras), where

he traded in diamonds and coral. He met Haider during Haider's attack on

Madras, provided him with inside information on Nawab Ali Mohammed's movements,

and built a strong rapport, ultimately obtaining a large house, numerous

privileges, and access to Hyder. However, he remained in Madras until 1770. It

also appears that he advanced a large sum of money to Hyder. Furious with the

British, who did not come to his aid when the Marathas attacked (he had signed

a mutual defense treaty with them in 1769), Hyder grew strongly anti-British.

Since the number of foreign mercenaries and supplies

obtained through the Dutch, Portuguese, and French was inadequate, Hyder looked

for other European allies to provide him with material support, skilled

officers to train his troops, technicians for the dockyards, and naval

equipment to support his growing navy. Goldsmith seems to have convinced Hyder

that he had the contacts to secure support from Europe, modernize his forces,

and counter the British and Maratha armies.

Goldsmith's return to Europe in 1771, following the British

falling out with Hyder, was to establish alliances with either Sweden, Denmark,

Prussia, or Spain. He appears to have had some correspondence with Denmark and

later traveled to Prussia, his homeland, where he stayed from 1771 to 1772.

There, he tried to enlist the support of the Prussian crown (presenting Hyder’s

letter praising German missionaries), but Friedrich II was busy with matters

concerning Poland. In the end, he managed only to recruit a Prussian officer,

Andre Hearton (Hardung), to be a fellow traveler and help execute his plans,

which you will soon realize were quite fantastic!

Failing to persuade Denmark and Prussia, Spain became the

next target for Goldsmith. The two Prussian representatives then visited the

Spanish embassy in The Hague in August 1773, requesting safe passage to Madrid,

and met with Viscount Herrera, the ambassador. Goldsmith introduced himself as

the plenipotentiary envoy of Haidar Ali, the Mysore Sultan, and, along with

Hearton, they aimed to meet the Spanish King and initiate a lucrative

commercial treaty between Mysore and Spain that could lay the groundwork for a

future "offensive and defensive alliance" between the two nations.

Goldsmith offered the lure of a monopoly on duty-free merchandise, as well as a

demand from Mysore for products Spain could supply, including military

equipment and mercenary support.

Armed with a recommendation from Herrera, the two diplomats

arrived in Madrid in December 1773 and met with the Spanish Secretary of State

Grimaldi. Once again, Goldsmith presented his proposals, outlining the

significant benefits Spain would gain, including duty-free trade and the free

provision of materials for constructing forts and warehouses in any port or

region of Mysore. He also emphasized that Hyder planned to procure Spanish

goods worth between 150,000 and 200,000 pagodas annually.

After reviewing the documents provided by Goldsmith,

Grimaldi met with King Charles III and received royal approval to proceed with

testing the proposal. The Secretary of State then ordered the procurement and

shipment of the specific goods requested by Hyder through Manila. The

Governor-General of the Philippines, Simón de Anda y Salazar, was instructed to

ensure the deal was executed smoothly, keeping the identities of Goldsmith and

Hearton, as well as the cargo's destination, confidential. Goldsmith and Hearton

were to be paid stipends and housed in Seville for about a year. The two guests

appear to have spent a significant amount of time in Spain, subsequently

spending nearly 9,000 reales de vellón on behalf of the Spanish crown. All this

did not go unnoticed by the British; their spies in Spain reported Goldsmith's

presence in Madrid, and an internal note stated that Goldsmith's

nineteen-year-old son had recently arrived in Madras from Holland.

Interestingly, the King was more interested in something

else from Malabar, and that seemed to be the primary focus. It was the

acquisition of an elephant, a collection of coins, and other exotic objects for

the Museum of Natural History, promoted by Prince Gabriel, his son!

In January 1775, the frigate Astrea departed for the

Philippines, carrying 3,000 rifles, flintlocks, uniform cloth, and caps for

Hyder's forces, along with 20,000 pounds of lead and 6,000 pounds of copper.

After arriving in Manila in August, Goldsmith and Hearton met with Governor

General Anda and Ramón Yssassi, his secretary, who also served as the

interpreter. Goldsmith gave Anda a parchment, apparently written in Farsi and

issued by Hyder, which would affirm his credentials. Although this appeared

somewhat suspicious, an Armenian trader in Manila, who had previous trade

relations with him, vouched for Goldsmith as a confidant of Hyder.

As part of the proposed treaty with Spain, Hyder (Goldsmith

appears to have drafted it in line with some previous treaties executed by

Hyder) stated that he would provide land, materials, and a location on a

riverbank for building a Spanish fort and factories, along with free residence

for Spanish subjects living and doing business there. Spain was to send

personnel to train the Nawab's staff in military affairs and trade, including

trading in materials listed and paid for in gold or silver, saltpeter, gemstones,

spices, or other locally sourced items of interest. The mutual trade would be

duty-free, and since Haider hadn't yet signed a treaty with any other European

power, it would be very advantageous to Spain.

Accordingly, the material from Spain was to be shipped from

Manila to Mangalore, accompanied by Goldsmith, Hearton, and a Spanish

delegation. Goldsmith insisted that Yssassi accompany him as Commander-in-Chief

and lead the delegation (Yssassi spoke French, which Hyder understood), which

Anda agreed to after much reluctance. Goldsmith cleverly latched onto Yssassi,

claiming that Yssassi had shown him around, introduced him to dignitaries, and

lent him money to buy gifts for the Nawab and his wives, so he owed him a

favor! Anyway, Anda finally agreed to release his secretary.

In January 1776, the ship La Deseada sailed for

Mysore with Ramon Yssassi, the ship's commander and emissary of the

Governor-General, Miguel Antonio Gómez, a military engineer familiar with the

Malabar coast, along with other crew members, as well as Goldsmith and Hearton.

They arrived at Mangalore on April 7, 1776.

|

| Reception at Mangalore by Adm Angria |

The boat was quickly unloaded, and the Mangalore governor, Cheg Ali, took delivery of the goods and various armaments. A British officer, Mor, arrived from Bombay and tried to threaten the Spaniards, but was rebuffed. The delegation was then formally welcomed by Hyder's admiral, Raghunath Angria. Goldsmith and Hearton retired to a large homestead. In May, the delegation received a formal summons from Hyder, and they proceeded to Gurpur with all the gifts, including four Arabian horses and chariots, which the Spanish monarch had gifted. By June, the emissaries, Yssassi, Teras (a warrant officer), and a few others traveled to Seringapatam with Hyder's cavalry. Antonio Gomez and the others remained in Mangalore.

Back in Mangalore, a bored Gomez watched life around him and

recorded events and matters in his diary, also adding some sketches. He also

noted troop and ship movements, as well as the various festivals and

communities. Soon, they were running low on reserves and money and faced

problems with a group member named Chrestien Fanleybe, who claimed to have

loaned money to Goldsmith and demanded repayment. Goldsmith had told Fanleybe that

he would be appointed as the Naval admiral of Mangalore!

In September, Gomez received news that Yssassi had died in

Seringapatam from a fever. Suspecting foul play, Gomez hired a Turkish fakir to

investigate for a fee. Although the fakir returned two months later, Gomez did

not reveal his report; however, he mentioned a rumor that Goldsmith had

poisoned Yssassi. It was also clear that the Spanish team had been confined in

Seringapatam and not allowed to leave by Hyder, possibly because they hadn't

offered enough bribes, and the gifts were not sufficient. Eventually, Teran,

the warrant officer promoted to head of delegation after Yssassi's death,

reported that pending matters were resolved and that they were returning with

payment for the goods. Along with them, they brought a large elephant, which

was Hyder's gift to the Spanish King, as well as coins and other items desired

by Charles III for his son's museum.

However, it was not practical; the elephant was too large,

and therefore, the Governor of Bednur Raja Ran (Rao) was ordered by Hyder to

obtain another. As a result, a baby elephant was acquired and given to the

Spanish delegation. Finally, the delegation was ready to sail back to Manila as

soon as the weather permitted.

Now, whatever happened to Goldsmith and Hearton? Did they

wash their hands of the Spanish delegation? It seems that Goldsmith, perhaps

after Yssassi, fell ill, decided to take matters into his own hands, and

claimed that the ship and the goods belonged to Hearton, the Prussian general.

Yssassi managed to uncover this deception, and as a result, the pair lost favor

with Hyder and fell into disgrace. Teran obtained authority from Yssassi just

in time and managed to turn the situation around. At Mangalore, Gomez faced

endless trouble from the defiant Chrestien Fanleybe, who continued to demand

his money and threatened to report the matter to the Nawab. This furor was

somehow suppressed, and Fanleybe was eventually silenced. As Goldsmith's

deception began to unravel, Gomez also learned from others that from the moment

the ship landed, Goldsmith had been claiming the vessel was Prussian and that

all the Spaniards were actually Prussian officers.

Anyway, Goldsmith and Hearton were expelled from

Seringapatam in February but managed to escape Hyder's wrath. They then

traveled to Bednur, but Hearton died along the way. Goldsmith was again on the

run after creditors in Bednur pursued him. Gomez reported that another Turk

appeared at his door looking for Goldsmith and the money he had lent him, in

exchange for being appointed as an interpreter. Finally, on March 25, 1777, the

Spanish frigate set sail, and after an uneventful voyage, arrived at Subic Bay in

the Philippines on June 23. Goldsmith, meanwhile, traveled across borders and

ended up in Cannanore or Tellicherry.

Meanwhile, Anda had passed away, and Pedro Sarrio, who

received the papers from Gomez and his team, submitted them to Spain with a

recommendation to proceed with the trade agreement. The chief accountant

recorded that the total expenses of the expedition to Mysore had reached at

least 100,000 pesos.

Was Goldsmith really trying to pull off a major diplomatic

scam? He attempted to pass off the delegation as German, took money from

Fanleybe and the Turk, lied to everyone, and failed to warn the delegation on

how to prepare for the meeting with Hyder. He also did not inform Yssassi and

Hearton about the difficulty of the journey to Seringapatam through dense

jungles. Interestingly, Cheg Ali, the governor of Mangalore, also died on the

trek to meet Hyder, while Gomez was in Mangalore. Was he truly a fully authorized

envoy appointed by Haidar Ali? Though that seems quite likely, the authenticity

of the 'Moorish' documents was never confirmed. The reports from the Turkish

fakir and the notes made by Teran have yet to be unearthed to clarify matters.

Again, we do not have Goldsmith's perspective since he left

no accounts. He claims to have lent money to Hyder, which was never repaid;

thus, he may have tried to recover his investment through this Spanish venture.

Nevertheless, he was alive until 1784, converted to Christianity and reappeared

at the EIC factory in Tellicherry under the new name John Baerindson, providing

intelligence on Tipu's (Hyder died in 1782) planned expedition to Malabar.

Thus, Spain's commercial venture in India ended not with

profits but with disappointment and significant losses. A draft treaty and a

baby elephant remained, along with a 138-page diary of his days at Mangalore

written by Gomez, complete with four sketches.

Would a trade pact with Spain truly have helped Hyder?

Probably not, since the Second Anglo-Mysore War took place in 1778, and

additionally, with France, Spain, and the Dutch supporting American

independence, an enraged Britain might have turned their focus to Manila.

Now we come to the baby elephant. As had been the case, the

monarchs in Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, the Vatican, Constantinople, and

other European countries were eager to acquire and showcase exotic animals,

such as elephants and rhinos. Charles III also wanted a few for his menagerie.

As it happened, he ended up acquiring two more from South India through

Governor Anda in the Philippines, while the Goldsmith affair was unfolding in

Mangalore. The first was a gift from the Nawab of Carnatic, Mohammed Ali Khan

Wallaja, in 1773, who was also trying to establish new alliances after a tough

period with the British. The second was also obtained from the Carnatic in 1777

after the death of the first, but it only survived in Madrid for a few months.

The King, grateful for these gifts, awarded Simon de Anda the right to display

an elephant on his coat of arms. Three Malabar Christians (former British

soldiers from Manila) were brought in to care for these elephants.

The third import was received through a royal request made

through Goldsmith to Hyder Ali, and it was the elephant gifted by the Governor

of Bednur in 1777, brought by Gomez to Manila. The five-year-old's name is

recorded as Sundapari (I believe it was actually Sundari, meaning

"pretty").

Problems began when Gomez arrived and discovered that Gov Anda was no longer alive. He handed over the elephant to Juan Francisco, Anda's nephew and estate executor, who, however, had no idea how to pay the bills for the elephant's care since the ship headed for Spain had already left. The new Governor General, Pedro Sarrio, did not plan to pay for it, as there was no official document from the King ordering the purchase of the pachyderm. Juan couldn't let the animal die, and soon, the arguments and correspondence turned scandalous. News reached Tomas, Anda's son, who was in Madrid, and he contacted the Secretary of India, Jose de Galvez, saying that Gov. Anda had planned to gift the animal to the King, and that the Manila bureaucracy was creating unnecessary obstacles. The news eventually reached the King, who ordered that all expenses be paid. Juan, after finally convincing Spain to pay for the elephant's transportation, personally took Sundapari to Cádiz in 1779.

As a result, a larger Sundapari arrived in Cádiz by the end of 1779, to be ceremonially housed at the Aranjuez stables. She was housed in the gardens of Aranjuez Palace in a new set of rooms. Sadly, she suffered from various ailments and died in September 1780. That marked the end of the Goldsmith caper.

The money spent on the elephant adventure was probably about half a million Reales—a small fortune. Further information on the continuing adventures of Isaac Goldsmith (or John Baerindson), the one time trader and Hyder's diplomat, isn't available in any of the old historic archives.

References

Haidar Alí: un intento frustrado de relación comercial entre

Mysore y Filipinas, 1773-1779 - Salvador P. Escoto

A Spaniard's diary of Mangalore, 1776-1777 - Salvador P.

Escoto

Treasures fit for a king - King Charles III of Spain's

Indian elephants Carlos Gómez-Centurión

The Elephant in the Archive: Knowledge Construction and Late

Eighteenth-Century Global Diplomacy - Birgit Tremml-Werner

Pictures & other documents referred – courtesy ARCHIVO

GENERAL DE INDIAS (SEVILLA, ESPAÑA).

Note: This article is based on the original archival research

conducted by the eminent (late) Prof. Salvador P. Escoto and the work of the

(late) Prof. Carlos Gómez-Centurión. My humble thanks to these great stalwarts.

4 comments:

It is mind boggling how people as far away as Manila, madras, Mangalore, Mysore and spain communicated and got things done in those days.

thanks sudhir,

all by mail couriered through ships. It took months, and by the time the letter arrived, the intent and purpose may have even been defeated.

How interesting, Maddy! Such a maverick , Goldsmith was!

Yes, indeed - Murali

Post a Comment