A Cultural or

political boundary?

I think most of us will recall that in the past, we had some strict rules when it came to marriages. People from Malabar would not marry

from families down South or up North. Let us take a look at that rule or custom

and see what it was all about during and after the days when the Calicut

Zamorins feuded with the Kolathunad rulers.

One can always argue if it was a rule or a custom, perhaps

the latter is a more appropriate usage, we shall soon see. The details come out

in various clarifications sought during the long discussions held to formulate

what is known and the Report of the Malabar Marriage Commission of 1891. It is

not my intention to discuss the practice of a Sambandham marriage, for it is a

complex and vast but totally misunderstood subject, so we can get to it some

other day.

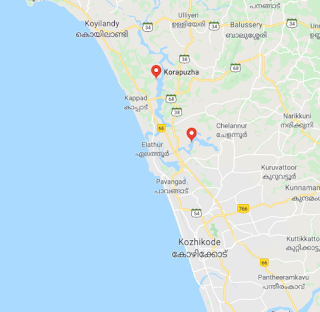

Rivers were considered natural barriers and divisive lines

between medieval feudal states. While women of South Malabar and Cochin cannot

go beyond Quilon in Travancore on pain of losing caste, those of north Malabar were

prohibited from crossing the Perumpula River towards the north and the Korapuzha

towards the south (Kora Puzha is roughly nine miles north of Calicut). Those of

Polanad were confined between Korapuzha on the north and Chalian River on the

south. The Putiyapalam River was respected by the ladies of the orthodox Nayar

families of Kizhakkumpuram and Vadakkumpuram. The list goes on, but we will

discuss the Kora Puzha rule, only because the discussion over that rule was

very well documented and widely debated.

How and why did this custom originate? The earliest

mentioned relate to the mythical Parasuma (of course!) who created the three

classes of women. According to the Kerala Mahatmyam, the Kora River, is the

"Ghara" in Sanskrit. The story is that Parasurama provided three

women by Indra, them being an Asura, a Gandharva and a Deva, proceeded on to

Malayala. He settled the first at Gokarnam, the second in North Malabar and the

last at Trichur. The progeny of these three women were (due to social levels or

hierarchy at Devaloka perhaps!) prohibited from associating with one another.

The sons of Deva and Gandharwa women may have mutual intercourse with the daughters

of Gandharwa and Deva females respectively, and vice versa in the Malayalam

country – viz. Kerala). Now note here

that the sons of Deva females are the Nayars of South Malabar, and the daughters

of the Gandharwa females are the women of North Malabar, because according to Kerala

Mahatmyam, the country between Cape Comorin and Ghora river was colonized by

the descendants of a Deva female and those of her six handmaids, and the

country between the Ghora river and Paysasini river in Kizhoor, at Kasargod, by

the descendants of a Gantharwa female and those of her six handmaids, and the

country between Payassini river and Ghokarnam in North Canara, by the descendants

of an Asura female and those of her six handmaids. This as you can see was the

legend attached to the divisions.

That was a myth, but perhaps the real reason lay in

the rivalry between the Zamorins and the Kolathunad Rajas. Many of the people

quizzed came up with this reason as the real basis, and the necessity for

absolute faithfulness by the supporting Nair and Tiya militia. Wifely ties

would weaken such faith and so, no liaisons should exist across the borders.

Further, property rights would mean that men in the South marrying up North can

lay claim to lands through their wives and vice versa!

Of course there were some who tried to explain that the

Northern Nair castes were superior, chaster compared to the South, that their

women had higher standing and so on which I would, like the marriage board,

take with a pinch of salt. The argument rested on the supposition that

polyandry prevailed largely in South Malabar whilst North Malabar was

comparatively free from it, and that the edict was issued to protect the purity

of North Malabar women. A curious fact was that all this and the Anuloma/Pratiloma

concepts were applicable only in Malabar and not to adjoining South Canara, so

it was not a rule which had any kind of broad religious or moral ground. Hence

it was just a custom.

Some went back to a period where there was a belief that N

Malabar women would be dishonored in the Zamorin’s country and connected the

belief to an event where a bunch of N Malabar women had gone to Calicut to

attend a feast or celebration, during which they were detained there and

married off to many Nairs in the palace. This was done in order to create a

clan which became the Zamroin’s personal staff. They are the ‘akathu cherna

nayanmar’ or Parisha Menon’s or todays Menon’s.

The furious Kolathunad raja, unable to physically retaliate

against his powerful rival, put in the ban on any of his female subjects from

ever again entering the Zamorin’s territory. His words on the occasion are

reported to have been somewhat to the following effect. "Into the

territory of the Zamorin, who is guilty of such gross misconduct as this, let

our women (subjects) not enter." A later generation, who perhaps did not

know, or were not informed of the reason for the prohibition, or, who, by lapse

of time, and because no fresh instance of the kind took place in the South

mis-paraphrased the Rajah's words into a prohibition to cross the Korapuzha—the

Southern boundary of Kolathnad.

Stories like this abound, for there is one siding with the

Zamorin as well. The relations between one of the Zamorins and a certain

Kurumbranad Rajah was, let us say friendly and there was much intercourse

between the two domains, so much so that it appears the Kurumbranad Rajah

succeeded in bedding a Tampuratti of the Zamorins's family. The enraged Zamorin

put in a travel ban towards the North!

There were some other complex issues too at stake relating

to Yagam performance as one explained- There are no Nambuthiris to the North of

Korapuzha and to the South of Aleppie river who can perform Yagam and kindred

ceremonies; therefore high caste Brahman women cannot travel beyond these

boundaries and consequently the Sudra dependents too, of these Brahmans are

prohibited from going further than the two limits.

While Korapuzha was the Kolathunad border many years ago, in

the 19th century it became an issue since Korapuzha was no longer in

the Kolathunad territory. The correct boundary between North and South Malabar,

for argument sake should have been the Kottakadavu (Marat River) and not the

Korapuzha, because, the country beyond the Kottakadavu and within the Korapuzha

forms the Southern portion of the Kurumbranad Taluk.

Petty religious issues were also brought up, for example the

Korapuzha required boats to cross it and they were all owned and rowed by

Moplah’s. In certain other rivers, they had Hindu Pitran rowers, so it was not

a problem. But at Korapuzha, they could not circumvent Moplahs. It also appears

that there was an event relating to some Kolathunad women being ‘ravished’ by

the Moplahs in the Zamorin’s kingdom!

Property rights were mentioned - In the olden time

Kolathunad extended up to Korapuzha and Kolathiri, who is said to have exacted

feudal services (military) from thirty thousand Nayars under him, thought it

wise to rule with a view to stop emigration of these feudal serfs, that to

cross that boundary for a female of North Malabar (who is, of course only

likely to propagate such serfs rightly belonging to his Swarupam) was to entail

excommunication.

The subsequent conquest by the Mysore Sultans also figured

in the arguments – One went thus - The dominion of the Zamorin was overrun by

Tipu Sultan, who converted many a Nayar to Islam. The Rajah of Chirakkal then

issued an order that no woman should cross the Korapuzha, lest she be

converted, and that no man of South Malabar should be admitted to a North

Malabar family on the belief that all in South Malabar (including the Zamorin)

had become converts to Islam!

The conclusions after the involvement of all the

representing nobles (my Great Great grandfather Vidwan Ettan Thamburan,

included) and educated men of that time, was as you can imagine, inconclusive.

If you are interested in hearing what my ancestor (who became the Zamorin only

a few years after the interview) had to say, well he was a deeply religious

person who believed in the caste system and furthermore, the Bhagavad Gita. A

very conservative and caste bound men, he said…

There exists no absolute objection to a Nayar woman of North

Malabar going South of Korapuzha.

The causes which led to this prohibition

appear to me to have been:

(1) The restrictions laid down by the two Rajahs (Zamorin

and Kolathiri)

(2) If the women were allowed to travel as freely as they

pleased, they would enter into all sorts of connections forbidden by caste

regulations and customary usage, which would undermine caste observances, and

would remove caste distinctions, so much so that all classes would be reduced

to the same level, and lead to other similar evils. It is clear from the

following quotation from Bhagavatgitha that if the women fall and become

degenerated it would be productive of enormous evil…

"0 ! Krishna! From

the increase of vice (even) family (chaste) women become sinners. 0! Descendant

of Yrishni (Krishna)! When women are bitten ("corrupted) confusion of

castes is the result. The wages of this confusion will be hell even to the race

of such as destroy the purity of families, for their forefathers will sink into

hell, being deprived of Pinda (funeral cake), TJdagam (holy water) and Kriya

(funeral rites). By these vices of the destroyers of families, which produce

mixtures of castes, the long established religious observances of castes and of

families are up-rooted."

The Malabar marriage act of 1896 was eventually enacted,

though it did not quite make an impact.The first man in North Malabar, who

tried ineffectually to break through the custom was the late Kuvukal Kelu Nayar,

a late Sub-Judge of South Malabar. His son Kunhi Raman Nayar, who was also

Sub-Judge of Calicut, too, failed in his attempt to take his wife to Calicut.

Thurston adds, though not referring to the apparent origins

of the Akattu Charna caste from Kolathunad – To this rule there is an exception, and of late years the world has

come in touch with the Malayāli, who nowadays goes to the University, studies

medicine and law in the Presidency town (Madras), or even in far off England.

Women of the relatively inferior Akattu Charna clan are not under quite the

same restrictions as regards residence as are those of most of the other clans;

so, in these days of free communications, when Malayālis travel, and frequently

reside far from their own country, they often prefer to select wives from this

Akattu Charna clan. But the old order changeth everywhere, and nowadays

Malayālis who are in the Government service, and obliged to reside far away

from Malabar, and a few who have taken up their abode in the Presidency town,

have wrenched themselves free of the bonds of custom, and taken with them their

wives who are of clans other than the Akattu Charna.

He then goes into detail about the custom of a Mannan being

the one to provide the ‘mattu’ or post mensuration period clothes to a Nair

woman, but does not quite explain how it applied to an Akattu Charna Nayar

woman. Perhaps she can have the mattu from any dhobi, not a vannan?

According to Kodoth’s studies - This prohibition on Women had by the turn of the turn of the twentieth

century turned into a source of inconvenience for the increasing number of Nair

men employed outside north Malabar. Men employed outside North Malabar or in

Madras resorted to sambandham with women in south Malabar owing to the

inconvenience of the rule. The first instances of women defying the rule were

in order to join their husbands and these women had to bear the pain of

ostracism. A few women did cross to join their husbands in Calicut. Chandu

Nambiar recalls that it was possible to break the taboo only because women of

the older generation took it upon themselves to violate the norm. They were

also willing to brave the censure involved. By the 1920s, women were crossing

the river without major social repercussions.

But with the passage of time, new marriage rules came into vogue

and old feudal rules disappeared, but even today you can see chaste Nair or

Tiya families asking questions about the geographic origins of the groom or the

bride’s family, during marriage proposals. In fact when two Malayalee’s meet,

the first question is where in Kerala the other is from!

References

Shifting the ground of fatherhood, Matriliny, men and marriage

in early 20th century Keralam – Praveena Kodoth

Nayars of Malabar – F Fawcett

Report of the Malabar Marriage commission 1891.

Castes and Tribes of Southern India, by Edgar Thurston Vol 5

Note: Today the Korapuzha is also known as the Elathur river

WISHING ALL READERS A HAPPY NEW YEAR

2 comments:

Makes very interesting reading in this lockdown.Though worked in palghat for about 20 years not aware of many bits of interesting palghat history.Thanks for enlightening.

Thanks Sudhir..

some of those old customs are so strange, when viewed today!!

Post a Comment