One of the earliest written documents referring to the details of Chinese and Arab trade with Malabar and the Malabar ports is the Chu fan Chi written by Chau Ju Kua. Though there is one other document, which is the reference provided by Suleyman the merchant, revised by Zayid Hasan of Siraf and Masaudi between the 9th and 10th centuries respectively, the Chau ju-kua (pronounced Zhao Rugua) book has special importance as this touches on the Chinese trade with Malabar.

The phrase Chu Fan chi means ‘Description of the barbaric (could also mean foreign) people’ and covers the Chinese Arab trade of the 12th and 13th centuries. I have referred to the English translation provided by Friedrich Hirth and WW Rockhill.

The phrase Chu Fan chi means ‘Description of the barbaric (could also mean foreign) people’ and covers the Chinese Arab trade of the 12th and 13th centuries. I have referred to the English translation provided by Friedrich Hirth and WW Rockhill.

First some background - The first mentions of Chinese traders comes from Ceylon which was also a focal point of Arabic Red sea traders. Early mentions of far eastern sailors can also be found in ‘Cosmas Indicopleustes’ which was written around the 6th century and mentions goods from China. It is also known that Canton had Arab & Indian colonies at the port as early as 200AD. Trade existed between India and China as early as 2nd century AD, over Northern Pegu (Burma) but this was mainly overland. Maritime trade with Chinese ships started in the early decades of the 7th century first via Siam (Thailand). Nevertheless there are allusions to extensive trade which Coriander mariners conducted between the shores of Malabar, Coromandel ports, Ceylon, Indonesia and even Indo-China even before that. Documentation though is very difficult to come by.

However Chinese accounts do mention sea trade with India as early as 120BC. Herein lay a strange anomaly. Probably due to errors or confusion with translation, many historic books talk about tribute being paid to Chinese kings. Dr G Banerjee in his book ‘India as known to the ancient world’ is emphatic in pointing out that tribute was actually confused with the word trade and it involved bilateral exchange of produce. So while many books talk of the mighty Chinese empire being paid tribute, the actual situation was a conduct of normal trade without any might attached to it. The main tributary countries to China were India, Arabia and Persia. Prof Hirth believes that port of Canton was in existence since 3 BC. India was known as Tien chu ( from Sanskrit Sindhu – Shindu) in Chinese writing.

Though one of the first Chinese to undertake a sea voyage and write about it was Fa Hien who  went from Hoogly in Calcutta to China in the early part of the 5th century, (He went from Hoogly to Ceylon, then to Java and finally Chinese shores, in a wind sailing ship) Documented Arab trade routes came up first in the 8th century from the port of Kia Tan and here one can see that the port of Kulam Mali or Quilon is the main stopping point in Malabar for Arab ships (However these were heresy information and the Chinese still did not have first hand trade with India. The route beyond Quilon, to the Red sea ports is missing or sketchy). At the same time earlier mentions that very large ships (Arab or Indian) were entering Canton harbor and that ladders many tens of feet high were needed to scale those ships for unloading have been found. As trade progressed, the colony in Canton had become Muslim and had numerous Persians and Arabs. Around the 9th century another port became popular, named Zeytoun. But by then the revolt in the area resulted in many of these foreigners fleeing China and settling down in West Malaysia.

went from Hoogly in Calcutta to China in the early part of the 5th century, (He went from Hoogly to Ceylon, then to Java and finally Chinese shores, in a wind sailing ship) Documented Arab trade routes came up first in the 8th century from the port of Kia Tan and here one can see that the port of Kulam Mali or Quilon is the main stopping point in Malabar for Arab ships (However these were heresy information and the Chinese still did not have first hand trade with India. The route beyond Quilon, to the Red sea ports is missing or sketchy). At the same time earlier mentions that very large ships (Arab or Indian) were entering Canton harbor and that ladders many tens of feet high were needed to scale those ships for unloading have been found. As trade progressed, the colony in Canton had become Muslim and had numerous Persians and Arabs. Around the 9th century another port became popular, named Zeytoun. But by then the revolt in the area resulted in many of these foreigners fleeing China and settling down in West Malaysia.

Chinese shipping started roughly between the 9th and 12th centuries and touched the Malay, Indonesian and other Far Eastern ports. The lucrative trade was run directly by the Chinese monarchies. By the 12th century Chinese junks (square in shape and built like grain measures) seem to have started calling at Quilon. By the 12th century the Chinese compare themselves to Arab ships stating that while their ships housed several hundred men, the ones from the Arab side were much bigger and housed a thousand.

Chau Jhu-kua, an inspector of foreign trade at the customs department in Quanzhou (Fukien – Fujian) a.k.a Zeytoun, then (Information collected from around 1211 and completed by 1225) documents (together with another man called Chou Ku Fei) for the first time whatever knowledge he has heard in the ports about the seas, the ports of call, the ships and the material traded. The second volume lists all the traded goods and their characteristics.

He states in the second book that Malabar exports cotton and spices in return for silk and Porcelain. While the cotton and other produce was of smaller quantities, pepper was sizeable (if you recall Marco Polo mentions that the amount of pepper that goes to China is 100 times more than what goes to Europe). So the trade with Malabar was robust and continues so until it reached an abrupt end in the 13th century was briefly reignited when Cheng Ho came in the 15th century and stopped again after the Portuguese came. It would be interesting how the pepper reached China after the 15th, it probably got re routed via Far East Asia, but that will be discussed in some later article.

Let us see what he has heard of and how he describes Malabar

Malabar (Nan-pi)

The Nan pi country is in the extreme south west. From San fo tsi, one may reach it with the monsoon in a little more than a month. The capital of the kingdom is styles Mie-a-mo (Malabar) which has the same expression as the Chinese expression Lissi.

The ruler of the country has his body draped, but goes barefooted. He wears a turban and loin cloth, both of white cotton cloth. Sometimes he wears a white cotton shirt with narrow sleeves. When going out he rides an elephant and wears a golden hat ornamented with pearls and gems. On his arm is fastened a band of gold, and around his leg is a golden chain.

Among his regalia is a standard of peacock feathers on a staff of vermillion color, over twenty men guard it round. He is attended by a guard of some five hundred picked foreign women chosen for their fine physiques. Those in front lead the way with dancing, their bodies draped, bare footed and with a cotton loin cloth. Those behind ride horses barebacked, they have a loincloth, their hair is done up and they wear necklaces of pearls and anklets of gold, their bodies are perfumed with camphor and mush and other drugs, and umbrellas of peacock feathers shield them from the sun.

In front of the dancing woman are carried the officers of the king’s train, seated in litters (bags) of white foreign cotton and which are called pu-toi-kiou and are borne on poles plated with gold and silver.

In this kingdom there is much sandy soil, so when the king goes forth, they first send an officer with an hundred soldiers and more to sprinkle the ground so that the gusts of wind may not whirl up the dust.

The people are very dainty in their diet; they have a hundred ways of cooking their food, which varies every day.

There is an officer called Han-Lin who lays the viands and drinks before the king, and sees how much food he eats, regulating his diet so that he may not exceed the proper measure. Should the king fall sick, through excess of eating, then (this officer) must taste his faeces and treat him according as he finds them sweet or bitter.

The people of this country are of a dark brown complexion, the lobes of their ears reach down to their shoulders. They are skilled in archery and dexterous with their swords and lances; they love fighting and ride elephants to battle, when they also wear turbans of colored silks.

They are extremely devout Buddhists.

The climate is warm, there is no cold season, Rice hemp, beans, wheat, millet, tubers and green vegetables supply their food, they are abundant and cheap. They cut an alloyed silver into coins, on these they stamp an official seal. The people use it in trading. The native products include pearls, foreign cotton stuff of all colors (i.e. colored chintzes) and tou-lo mien (cotton cloth).

There is in this country a river called the Tan shui kiang which at a certain point where its different channels meet becomes very broad. At this point its banks are bold cliffs in the face of which sparks (lit stars) can constantly be seen and these by their vital powers fructify and produce small stones like cat’s eyes clear and translucid. These lie buried in holes in these hills until some day they are washed out by the rush of a flood when the officials send men in little boats to pick them up. They are prized by the natives.

The following states are dependent on this country of Nan pi. (City names in brackets provided by Rockhill, and are assumptions)

Ku-Lin (Quilon)

Fong ya Lo (Mangalore)

Hu Cha La (Gujarat)

Ma li mo (Malabar)

Kan Pa i (Cambay)

Tu nu ho (Salsette island - Bombay)

Pi li sha ( Broach)

A li jo ( Eli mala – Cannanore)

Ma lo hua (malwa)

Au lo lo li (Cannanore or Nellore)

The country of Na Pi is very far away and foreign vessels rarely visit it. Shi lo pa chi li kan father and son, belong to this race of people, they are now living in the Southern suburb of the city of tsuan (chou fu)

Its products are taken thence to ki lo tu sung and San fo tai abd the following goods are exchanged in bartering for them: Ho-chi silks, porcelain ware, camphor, rhubarb, cloves, sandalwood, cardamoms and gharu-wood.

Ku-lin may be reached in five days from the monsoon from Nan Pi. It takes a tsuan chou ship over forty days to reach lang Li (Lan wuli) there the winter is spent and the following year, a further voyage of a month will take it to this country.

The customs of the people on the whole are not different from those of the Nan Pi people. The native products comprise cocoanuts and sandalwood, for wine they use a mixture of honey with coconuts and the juice of a flower which they ferment.

They are fond of archery; in battle they wrap their hair in silken turbans.

For the purpose of trade they use coins of gold and silver, twelve silver coins are worth one gold coin. The country is warm and has no cold season.

Every year ships come to this country from San fo Tsi, Kien-pi and Ki-to and the articles they trade are the same as in Nan pi.

Great numbers of Ta-shi live in this country. Whenever they have taken a bath they anoint their bodies with yu-kin as they like to have their bodies gilt like that of the Buddha.

Preliminary comments

Strangely little is written about Ku Lin (just the last two paragraphs), the place where they docked, but much is written about Ku Li or Calicut. This probably signifies the might of Calicut and the Zamorin’s control in the pre 12th century period.

The Nair family that settled in China is very interesting – Shi lo pa and Chi li kan. Though many historians refer to them as Nair’s it is very difficult to infer so from the sounds of the names. I do recall an ambassador Narayana from the Zamorin in the 15th century. It is noted from the translator’s comments that after the arrival of the two Malabar people in China, the trade increased drastically.

Tanshuikiang River – Which could that be with the mountains and hills behind it? Was it the Chaliyam River, Korappuzha or perhaps something bigger from the past? It could very well be. Maybe it is the river mentioned by CKR in his comments as flowing through the middle of today’s Calicut.

The golden amulet is noticed by many visitors. Vasco DeGama (Correa) mentioned that it was so heavy that it needed a person to support his arm.

It is unlikely that the Zamorin had a retinue of female guards. So were the women guards some sort of fanciful thinking? The first woman warrior mentioned in Malabar history was Unniarcha, to my understanding, but of course there were others before that.

The mention of silver coinage is a little strange. I do recall from Ma Huan’s book that 12 silver coins is equal to one gold coin in the 15th century. But until then Silver seems to have held up as main monetary token. This somehow contradicts mentions of that period that barter was the main method used by Coromandel traders. Probably large volume trade was bartered, and coins were used for smaller trade.

Officers carried in palanquins or riding on horses? That is indeed strange for there are hardly any other mentions of Malabar kings and officers on horses which were only popular and suitable in hard soil as found in neighboring Vijayanagar and Chola regions. Elephants of course are quite often mentioned in other accounts.

Cats eyes from the waterfall? Waterfalls were not unique to Malabar for such an impression to be made and documented. As Rockhill states, much of what Chau Ju Kua heard was from Arab traders who mentioned only what they wanted the Chinese to know, not necessarily the whole truth.

Han lian – officer seems to be some kind of Moosad vaidyar who was the personal physician. They existed well until the 19th century as personal Ayurvedic physicians. However the sampling of faeces is pretty new and totally unlikely (the rules of pollution would never allow that), it must have been imagination. The Zamorin wearing a white turban is also a new observation.

The great numbers of Ta-shi living in Quilon is again a very interesting observation for Ta-shi are Arabs. But Arabs anointing their bodies with oil is pretty rare but quite possible.

In another part of the book, it is mentioned that the Quilon people did not tie their hair up on top, wearing them loose compared to Malabar people and wore red leather slippers.

Salsette Island incidentally is today’s Greater Bombay. See the wikipedia article for details.

Nan pi is Nampi (as testified by Ma Huan in his book about Cheng Ho’s visit) – or land of the Nampoothiris? It is interestingly stated here in this book that the supremacy of the Nair country extended to Sri Lanka (Si Lan) and the other places listed thouygh it is very doubtful from a factual viewpoint.

About the people being Buddhists one should note that Chinese writers according to Rockhill use the word Fo which is transliterated to Buddha, but may just mean ‘God’.

A clarification about Zeytoun and Canton is needed here. Some historians mentioned that they are the same place, i.e. Quanzhou or Guangzhou, but others confirm that Zeytoun (Xiamen or Amoy now) came about only in the 10th century. Note that they had other names too, Canton was Chin or Sin-kalan or Khanfu and Zaytoun was Ts'iian-chow or Chinchu in Fukien. Hangchow or Hangzhou was a third port, close to Shanghai. Canton is to the south, Hangzhou up North and Xiamen between them.

The word Satin comes apparently from Zaytoun as it originated there.

References

India as known to the ancient world – Dr Gauranganath Banerjee

Chu Fan Chi - Chau Ju Kua - F Hirth and WW Rockhill

China in Word history – S A M Adshead

Pics - from the net, google images - thanks to the uploaders

Most Malayalees today would naturally assume that the word Changatham is the base for the term Changathi or friend. One thing I am not too sure is if the word Changathi evolved from Changatham though it may very well have. While the natives of Travancore usually stick to words like Snehithan or loved one, the term loosely used for friend in Malabar is Changathi or its Moplah version Changayee. In reality, the word Changatham has meanings far beyond friendship. Let us take a look, and this will takes you many centuries back, to the martial days of Nairs, the fighting clan of Malabar (I must also mention here that there are some historians who believe that there were even Changathams comprising Thiyya caste warriors in North Malabar).

Experts opine that the word Changatham itself came from the Sanskrit word Sanghatta. The term in Malayalam means a moral binding or union between persons, to start with. So as you can see, there is sense in assuming that the word Changathi evolved from Changatham. However the term Changatham signified a special martial group of Nair’s (hopefully you recall my article on Chavers) well before the 13th century. I state this upon the basis that the terms Changatham and Chaver can be seen in the Payyannur pattu (that will follow in another blog) and hence existed in those ancient days. Now what did they do? Various writers and historians account for the fact that Changathams took the roles of body guards, guides and mercenaries.

Some historians account that Changathams actually provided protection for money; otherwise termed kaval panam (Logan calls it Kaval Phalam – associated with Convoy guarding). This ‘kaval panam’ was provided by wealthy individuals, traders & caravans, and curiously even single women (such as wealthy but excommunicated Namboothiri women – I was a bit mystified by this, but the Malappuarm gazetteer documents so). According to historians Raghava Warrier & Rajan Gurukkal, the systems of hundreds and thousands that supported each chieftain gave way to Changathams after the Cheraman Perumal’s time.

Now a general explanation on various militias around Calicut - Each Swarupam had its own fighting force and Kalari. The Venad force was known as Janam or a risippiti Janam. The Sammotiri or zamorin, the ruler of Kozhikode, had constituted the fighting forces under different categories- Grama Janam, Lokar, Chaver, Akampati and Changatham. The Grama Janam could have been the militia of Desavazhies and there are references to a number of 'Grama Janams' in the list of invitees to the investiture ceremony of the Samootiri. The Lokar seems to be the military or paramilitary force in and around the capital, available to the ruler at short notice. The regulars of the Samootiri were constituted into Chaver and Changatham. The 'Changatham' served as the 'Akampati Janam' or retinue of Samootiri. The special force of Chaver served as the suicide squad or 'companions of honour'. These soldiers were always ready to lay their lives for the sake of the king.

Now a general explanation on various militias around Calicut - Each Swarupam had its own fighting force and Kalari. The Venad force was known as Janam or a risippiti Janam. The Sammotiri or zamorin, the ruler of Kozhikode, had constituted the fighting forces under different categories- Grama Janam, Lokar, Chaver, Akampati and Changatham. The Grama Janam could have been the militia of Desavazhies and there are references to a number of 'Grama Janams' in the list of invitees to the investiture ceremony of the Samootiri. The Lokar seems to be the military or paramilitary force in and around the capital, available to the ruler at short notice. The regulars of the Samootiri were constituted into Chaver and Changatham. The 'Changatham' served as the 'Akampati Janam' or retinue of Samootiri. The special force of Chaver served as the suicide squad or 'companions of honour'. These soldiers were always ready to lay their lives for the sake of the king.

The term Changatham apparently originated from Sanghatta in Sanskrit and this was used by the Portuguese in their chronicles – Jangada, Sanguada or Jancada as used by the Franks was a traditional arrangement in Kerala concerning the terms of service of certain persons. Readers would be surprised to note that the Portuguese also started employing the Jangada and they had similar Jangada mercenaries in their forts. Whiteway (The rise of Portuguese power in India, 1497-1550 - By Richard Stephen Whiteway Pg 12) confirms that the Portuguese had a Jangada for each of their Malabar forts and it was their duty to defend anything entrusted to their with their life and that it was a serious matter to kill them as it involved in a blood feud with all their relatives (Koodi paka). Once the Koodipaka situation erupted, the affected Nair males shaved their heads and entered into a revenge fight unto death. Whiteway also writes about De Souza’s attack on the Telicherry temple (Pg 284) where the two Jangada groups that were guarding the temple were drawn away by another fight and how one of these groups returns the next day, with the chief dressed ornamentally and accompanied buy 10-12 Jangada Nair’s.

Hobson Jobson & Yule’s dictionaries state –

Thus :

1543. — " This man who so resolutely died was one of the jangadas of the Pagode. They are called jangades because the kings and lords of those lands, according to a custom of theirs, send as guardians of the houses of the Pagodes in their territories, two men as captains, who are men of honour and good cavaliers. Such guardians are called jangadas, and have soldiers of guard under them, and are as it were the Counsellors and Ministers of the affairs of the pagodes, and they receive their maintenance from the establishment and its revenues. And sometimes the king changes them and appoints others." — Correa, iv. 328.

c. 1610. — "I travelled with another Captain . . . who had with him these Jangai. who are the Nair guides, and who are found at the gates of towns to act as escort to those who require them. . . . Every one takes them, the weak for safety and protection, those who are stronger, and travel in great companies and well armed, take them only as witnesses that they are not aggressors in case of any dispute with the Nairs." — Pyrard de Laval, ch. xxv. ; [Hak. Soc. i. 339,and see Mr. Gray's note in loco].

1672. — "The safest of all journeyings in India are those through the Kingdom of the Nairs and the Samorin, if you travel with Giancadas, the most perilous if you go alone. These Giancadas are certain heathen men, who venture their own life and the lives of their kinsfolk for small remuneration, to guarantee the safety of travellers." — P. Vincenzo Maria, 127.

If you have read my blog on the Kuri systems of Kerala., you would have come across Changathi Kuris’ obviously this was meant for a group of Changathis from an erstwhile Changatham.

The Kerala government text book says - The Yogams (councils) of the Namboothiri trustees of temples and temple lands and their privileges were together called Sanketam. In the absence of sovereign authority of the government the Sanketams became real rulers. They administered law and justice in their jurisdiction. The Changatham was a group of warriors who ensured protection and safety to a Desam and to the Sanketam property. Like the Chavers, Changathams were also suicide squads. They were rewarded with a share from the offerings that were received at the temple. The share was called "Kaaval Panam" (remuneration for guarding) or Rakshabhogam. It was with the military backing of these Changathams that the Brahmins established social and political hegemony.

In the 13th century ballad “Payyannur pattu”, you see a mention of these groups, Chavalari pole Niyakaippuram, Changatham venam Perikayippol. More on this and the ballad later. So these local militia with some of their old features continued to exist in the subsequent medieval period of the principalities in the name of 'Changatham', 'Chaver', 'Lokar' and 'Akampati Janam'. It is believed that these bands of soldiers belonging to different communities in the middle ages must have risen out of such companions of honour, originally conceived as body guards of the rulers and local authorities and developed into a landed aristocracy supporting the established order with military power.

Herman Gundert in his Malayalam English dictionary from 1872, defines Sangatham as – Responsible Nayar guide through foreign territories. He lists Changathi as an unrelated entry to Changatham and explains it as companion with a feminine gender as well - Changayichi. Interestingly when used as Changathamakuvan (Gundert gives an example Kamsane konna Goplane kamsanu Changathamakkuvan) it means to ‘send one along, to kill likewise’.

So that is the Nair definition – Companion of honour, closely bonded with a dissoluble bond. Typically this companionship was between males. So when somebody says or sings ‘Changatham koodan vaa’ it means much more than passing friendship…As I explained earlier, ‘koodipaka’ goes past many generations..

Changadam – These famous Malabar rafts (paired longboats) called Changadam are different

from Cangatham, but here again, looking at Barbosa’s account translated in English by ML Dames provides an interesting aside. It states that Changadam is two boats joined or lashed together and this bond is synonymous with the moral bond between two Changatham members (Pgs 48, 49). Dalgado’s Glossario ( pg 181) further gives examples of Vasco Da Gama’s sailing on Changatham’s to the Calicut shores, and states that Yule considers this one of the rare preserved Dravidian words, preserved from classical antiquity even though it is admitted that it may have evolved from the Sanskrit Sanghatta. The Portuguese introduced the Jangada boats later in Brazil, though they used the same term for the Malayali Kattamaram or roped up log rafts.

from Cangatham, but here again, looking at Barbosa’s account translated in English by ML Dames provides an interesting aside. It states that Changadam is two boats joined or lashed together and this bond is synonymous with the moral bond between two Changatham members (Pgs 48, 49). Dalgado’s Glossario ( pg 181) further gives examples of Vasco Da Gama’s sailing on Changatham’s to the Calicut shores, and states that Yule considers this one of the rare preserved Dravidian words, preserved from classical antiquity even though it is admitted that it may have evolved from the Sanskrit Sanghatta. The Portuguese introduced the Jangada boats later in Brazil, though they used the same term for the Malayali Kattamaram or roped up log rafts.References

Herman Gundert – English Malayalam Dictionary

Hobson – Jobson Dictionary

Malabar – William Logan

The rise of Portuguese power in India, 1497-1550 - By Richard Stephen Whiteway

Glossario - Dalgado’s

Duarte Barbosa Chronicles – ML Dames translation

Kerala history – Raghava Warrier, Rajan Gurukkal

Pics - Thanks to

Mammotty & his warriors – Pazhassi Raja an upcoming film

Boats of the World - By Sean McGrail Pg 268

A number of historians have written over the years about the trade systems that flourished in the Indian Ocean. These days I am happily immersed in the perusal of some fascinating books covering this subject in much detail.

But then, so many hours and days studying traders and reading about ships in the Indian Ocean was making me seasick, so I decided to spend a little time researching another interesting part of the Malabar world that made it all possible. All this trade or at least a major part outside the spice business happened only because of a natural formation in the Western Ghats or Sahyadri mountain range called the Palghat gap, which was the pass permitting the land route for trade. Some eminent historians have focused on the role the gap played in enhancing the trade in the past, but there were hardly any documentation in the public domain, and all this made me curious enough to divert my thoughts for a while to my mater land – Palakkad (Palghat).

Many of you would have driven through the Kuthiran Churam between Palakkad and Trichur, It was quite adventurous in old days, not anymore. As child I still remember how the transport buses labored climbing the steep slopes and stopped to change the water in the radiator. I remember how cars also stopped at the cool summit and drivers scurried up to break a coconut for luck at the Ayappan temple. And I remembered the famous story of how a man escaped robbers by making them get off the car to push it at the steep Kuthiran slope.

The Western ghats stretches between north of Kerala and the very south. These ghats isolated  and protected Kerala over the years. While the Tamil Kongu regions were conquered by many dynasties and kings from the north, Kerala remained aloof and was not inaccessible from the North and the East; in fact the first and only major invasion of Malabar occurred when the Mysore Sultans came in through the pass.

and protected Kerala over the years. While the Tamil Kongu regions were conquered by many dynasties and kings from the north, Kerala remained aloof and was not inaccessible from the North and the East; in fact the first and only major invasion of Malabar occurred when the Mysore Sultans came in through the pass.

Having looked at some geography, let us get back to the historic trade aspects. Roughly between 3000BC to about 40AD, Arab traders monopolized the Indian Ocean trade zone together with their Indian counterparts. It was finally Hippalus that helped Romans break the iron grip (though according to some Indo Roman trade existed many hundreds of years before that). The Romans continued independent trade until the 4th century, after which the Arabs wrested back the ascendancy. The first recorded use of Palakkad gap as a conduit for trade takes us to these periods, the turn of the century to the 4th.

|

| Palghat gap - a great photo showing the gap - contributed by Premnath Murkoth |

So as you can see, the Palakkad gap or mountain pass is the only gap between Kerala on one side and Tamil Nadu on the other. But did the Romans and Greeks conduct direct trade with the East coast? No, and the reason was the tricky area south of Cape Comorin, a place well known to ancient mariners. The area was difficult to circumvent due to rock formations (probably the Ramn Sethu Bridge existed then), lack of wind support for sailing and possibly nuisance from the pirates and the such. Even the Arabs did not venture past Tuticorin, maybe there were some loose agreements not to or the risks outweighed the opportunities. Nevertheless, the trade existed between Malabar ports and Red sea ports. While the early mariners kept close to the land shores to reach Gujarat and Malabar, the discovery of the monsoon winds brought both Arab and Greek - Roman mariners to Malabar sailing with the winds, reaching faster and safely.

So what was going on in the Kaveri valley and how did the trade guilds of Malabar access it? To understand that one must take a look at the periplus, the ancient manual of the sea. It explains all the sea ports of Malabar upto the Arikamedu port or Padouke. Here was where they made earthen ware to Roman specifications (first examples of outsourcing - And you may also recall my notes on the Pompeii Lakshmi).While many people studying the pottery and jewelry designs conclude that there was a Roman expatriate population living there, the story is still not complete and excavations continue.

Now how did the trade partners in the East coast get their goods across to the west coast? Land caravans took the goods to Coimbatore and from there it passed over land through the Palghat gap. Ships & boats did sail between Arikamedu and Muziris, but they were indigenous, possibly Marakkayar sailors.

The Romans knew of these South Asian ports and had been trading with them for ages. To a certain extent they integrated into the minds and psyche of the Tamil communities as Yavanas, contributing rich folklore in the process. Somewhere in the past this ceased, probably due to the strengthening of the control of waters on the east side. Muziris was one of the key ports and what the Greeks and Romans wanted were beads and gemstones like garnets and diamonds from the Kaveri basin. Indians though needed the gold and silver and were happy to exchange stones for gold. This healthy trade drained all gold reserves in Rome and you may recall the famous cribbing by Ptolemy. Peter Francis a bead specialist states that Bernike and Egypt traded beads with South India, stretching between 2AD and 3BC. Garnets, Emeralds (Beryl) glass and quartz beads, handicraft work originated from Arikamedu, Kodumanal, passing through the Palakkad gap and reaching Muziris for sea transport to the West. Sangam literature was first to mention this gem industry carried out by the ‘Pandukal’ and all this basically came to light with the discovery of Arikamedu. The Pandukal were metal smiths & gem smiths. Kodumanal another manufacturing location, now being excavated, also called as Kodumanam was key. Kodumanal curiously had all the raw material for the gemstone business though Arikamedu had not.

The Romans knew of these South Asian ports and had been trading with them for ages. To a certain extent they integrated into the minds and psyche of the Tamil communities as Yavanas, contributing rich folklore in the process. Somewhere in the past this ceased, probably due to the strengthening of the control of waters on the east side. Muziris was one of the key ports and what the Greeks and Romans wanted were beads and gemstones like garnets and diamonds from the Kaveri basin. Indians though needed the gold and silver and were happy to exchange stones for gold. This healthy trade drained all gold reserves in Rome and you may recall the famous cribbing by Ptolemy. Peter Francis a bead specialist states that Bernike and Egypt traded beads with South India, stretching between 2AD and 3BC. Garnets, Emeralds (Beryl) glass and quartz beads, handicraft work originated from Arikamedu, Kodumanal, passing through the Palakkad gap and reaching Muziris for sea transport to the West. Sangam literature was first to mention this gem industry carried out by the ‘Pandukal’ and all this basically came to light with the discovery of Arikamedu. The Pandukal were metal smiths & gem smiths. Kodumanal another manufacturing location, now being excavated, also called as Kodumanam was key. Kodumanal curiously had all the raw material for the gemstone business though Arikamedu had not.The bead traders were called ‘manivanakkan’. The raw material according to Peter Francis apparently went to Kodumanal, were crafted and then sent through the Palakkad pass to Ponanani. From there it went by boat to Muziris and by ship to red sea ports. Some went by sea from Arikamedu to Muziris and thence to red sea ports. Many present day historians and archeologists like S Suresh are of the opinion that the actual transshipment center before the material moved to Muziris was Kovai or Coimbatore.

As Dr. Suresh says, "Evidence of trade, diplomatic and cultural relations between India and Rome are found especially in southern India. And within South India, a large percentage of this evidence has been unearthed in the Kongu region, which today forms a large portion of the district known as Coimbatore". Vast amounts of Roman coins and other artefacts have been discovered around Coimbatore. Take the coin that is engraved with an image of Julius Caesar, found near the city. A one of a kind coin, it is the only one found in all of Asia. An overwhelming majority of such artefacts have been discovered in places that include Pollachi and Vellalore. Pollachi is in fact the place where the first recorded find of a Roman coin anywhere in Asia was discovered!

The Romans were drawn to India, and not just for her spices. Gem stones, textiles, ivory, ebony, iron and steel, and even peacocks were all sought after by the Romans from the Indian sub-continent. Pepper and other Indian spices, were largely found in southern India. In exchange for her merchandise, the country chose to receive gold coins and fine Roman wine. As Dr.Suresh puts it, "There was a scarcity of gold and silver in Southern India even way back then. And these were heavily in demand by South Indians. This aspect of history has changed very little even in present times!"

Going back to those days, Kongu country had vazhi’s and peruvazhi’s. These valis or vazhi’s were part of the huge roads and highway network. The most important was the Rajakesari Peruvazhi. See here for the roads. It was this road route that brought to Malabar diverse people like the Palghat Brahmins (Scribes, cooks and scholars), Chettairs and Mudaliar traders from the Coromandel, to name a few. The Konganpada came down this route and fought the people of Palakkad and lost, even today we have the annual Kongan Pada festival at Chittur- palghat.

Now you can imagine why the very location of the Palakkad fort was of prime importance to Hyder Ali and Tippu Sultan (note here that the Zamorin had cleverly used the Palakkad gap earlier to get his goods across to other ports in the East to circumvent the VOC blockade and surely Hyder saw that). The major road entry to Kerala from the East in the medieval times was through the Palakkad gap. Control of this access point to Kerala was critical and it was for this reason that a fort was needed. Remember that in the past many forts were built for sea entry protection. The Portuguese, the Dutch and the English built the first sea forts, but the later ports were all for land trade control. For a detailed story on the Palakkad fort refer my earlier article on this subject.

Notes:

While many people mention that the Palakkad gap is the only gap in the Western Ghats or Sahyadri Mountains, there is a smaller gap (1500ft) called the Shenkottai gap.

I have loosely used the words Palghat & Palakkad. Both mean the same and Palghat is the earlier English term.

References

The archeology of seafaring in ancient South Asia - Himanshu Prabha Ray

The Bead site – Peter Francis

Roman Karur – R Nagaswamy

Kodumanal today

Archeological sites Tamil Nadu

Map of the Western Ghats - Google

Some of my previous articles covered the Indian Ocean maritime trade and key players like the Maghribis, the Karimis, Marakkars, the ship building facilities at Beypore and so on. In almost all the cases, we saw that the traders, the sailors and merchants were of Moslem, Jewish, Christian or foreign extract. But this blog is about a non Moslem ship owner, ship owners whom the people, especially Arabs of those times termed a Nakhuda. Strangely all there is in the Genizah records, is a brief mention with his name and not much more. To make some sense out of it is difficult, but at least we can get an understanding of the facets of trade and the involvement of the individual in question.

Normally these ship owners did not participate directly in the trade; they just owned the ship and leased it via the captain probably raking in a percentage of sales for its use.

Normally these ship owners did not participate directly in the trade; they just owned the ship and leased it via the captain probably raking in a percentage of sales for its use.

This story again takes us back to the times of Abraham Ben Yiju (some think it is more correctly pronounced as Yishu) Asha or Ashu and the master of the Geniza records SD Goitein. It is now a good time to mention again that some experts like Roxani Eleni Margariti mention that Yiju lived in Pantalayaini Kollam and not Mangalore. If you recall, I had provided a perspective about this particular port in an earlier blog.

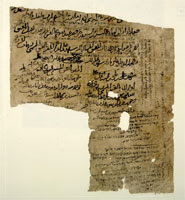

SD Goitein (in his paper - From Aden to India – Specimen of the correspondence of the India traders of the 12th century) transcribes a letter sent by Yiju to Madmun in Aden. The letter is dated 1146/1150AD. Paper was difficult to come by and expensive at those times, Indian scribes used palm leaves and iron nail based pens to record the Granthavari’s. Ink & paper were used only by the other traders. The same paper and every available inch of it was used by sender and receiver to record their communication which was painstakingly written in fine Arabic script (Sometimes scribes recorded the replies, not the trader himself). Now considering that the time between voyages and thereby correspondence can be one full calendar year, you see thoughts across large time spans in one parchment. The paper used is grayish in color or brownish. Sometimes you can even see that the discussion is suddenly cut short due to paucity of paper. Typically these scrolls were 10*70 cm and most possibly rolled up.

These papers from the Genizah at Cairo survived only because the lord’s name was on them  (and hence consigned to the Geniza for appropriate future action) and today we are fortunate to have bits of those parchments to peruse.

(and hence consigned to the Geniza for appropriate future action) and today we are fortunate to have bits of those parchments to peruse.

In the letter, Yiju says ‘I sent you this on the ship of the Nakhodah Ramisht one bag –in the ship of Nambiyar (ani) one bag and in the ship of Al – Muqaddam one bag. So we know now that the mystery ship owner is one Nambiayar

Ranbir Chakravarthi, eminent historian analyses the ship owner in a little bit more of detail in his paper and states (Nakhudas and Nauvittakas: Ship-Owning Merchants in the West Coast of India (C. AD 1000- 1500)) In addition to Fataswami (Pattani Swami as clarified by Amitav Ghosh in his book In an Antique land) and Fadiyar, Nambiyar is the third Indian (Hindu) ship owner that we come across in the correspondence between ben Yiju and Madmun. Nam-biyar's ship(s) too sailed between the Malabar coast (from Mangalore or some other ports) and Aden. That Indian ship owners did participate in the shipping network across the high sea can hardly be missed. Although it is true that only a handful of Indian ship-owners are known from the Geniza papers, which speak much more regularly of Jewish and Muslim ship owning merchants.

You may also recall from the earlier Ben Yiju article that Yiju was assisted by Sesu Chetty, a Nambiar and a Nair in his activities in Manjarur. Was this Nambiar ‘the’ ship owner? How did a Nambiar take up a Vaishya trade, which was very uncommon? Nairs & Nambiyars in those times, unlike today took up only martial activities, not trade in North Malabar. Was he a ‘benami owner’ in the Yiju coterie? Does that signify that Ashu was from Kolathunad? Does it mean that Nambiyar was in Pantalayani Kollam and not Mangalore? Considering that a Nambiyar trader existed in P Kollam in 1150, does it mean that P Kollam was beyond the Zamorin’s governance? Very mysterious indeed but unfortunately no information could be obtained to identify this ship owner or answer the above questions though one can come to certain conclusions.

It is likely that Nambiar operated in Mangalore, rather than Pantalayani, for Kollam was under the suzerainty of the Zamorin. It is also very likely that the Nambiar was a ‘benami’ (only by name) partner of Ben Yiju for he would have had great difficulty speaking Arabic and conversing with the traders like Madmun in Aden. Note here that the Nair/Nambiar community was not usually conversant with Arabic and such foreign languages; did not travel into the oceans and they were at best conversant in Malayalam and Sanskrit and were busy with the raja’s armies. So the relationship does look intriguing.

To understand the role Nambiyar may have played, one must also look at the three individuals in question, Ben Yiju himself, Fattanswami and Fadiyar. Fattanswami is Pattanaswami or lord of the ports. Strictly speaking it could have been a rich Chetty (perhaps Sheshu Chetty mentioned in the Yiju letters) ship owner and Pattanaswami or port master could just have been a common title as stated by Parkin & Barnes (Ships and the Development of Maritime Technology on the Indian Ocean - By David Parkin, Ruth Barnes – Pg 53). Fadi yar according to Goitein papers had a number of ships and could have been a Persian and not of Indian origin. It could not have been a ‘vadiyar’ or teacher, in my opinion.

It was relatively easy for these rich traders or Nakhudas to live and operate off the Malabar ports. Many of them distinguished themselves and had monuments named after them. Note here that the Mithqualpalli (Kuttichira mosque) in Calicut was named after the Nakhuda Mitqual, a 14th century Arab merchant. The masjid in Beypore was built by a Nakhuda in 1132.

All in all, pretty unlikely to have a Nambiyar as a Nakhudah, but then future outputs from the Genizah study may cast more light on this matter, some day.

References

Abraham and Asha

The Cairo Genizah

Notes: Documents from the Cairo Genizah date from the 9th through the 15th centuries. They catalogue the social, cultural, and  religious lives of Jews around the Mediterranean basin. The fragments were discovered in the late 19th century in the Ben Ezra synagogue in Fustat, a neighborhood in Old Cairo. Many of the fragments eventually wound up at Cambridge UK and many came to North America. Some fragments even have Indian languages such as the one shown. It could be Gujarati text.

religious lives of Jews around the Mediterranean basin. The fragments were discovered in the late 19th century in the Ben Ezra synagogue in Fustat, a neighborhood in Old Cairo. Many of the fragments eventually wound up at Cambridge UK and many came to North America. Some fragments even have Indian languages such as the one shown. It could be Gujarati text.

Nākhudā (when Anglicised, also written Naghdeh, Nakhodeh, Nakhooda, Nakhoda, Nakoda and Nacoda) is a term originating from the Persian language which literally means Captain. Derived from nāv boat (from Old Persian) + khudā master, from Middle Persian khutāi a 'master of a native vessel' or 'Lord of the Ship'. Historically, people with this epithet are Muslim and Kamili Jewish ship owning merchants of Persian origin, known to have crossed the Persian Gulf to trade in other coastal areas of the world. Besides Iran those with the surname Nakhuda can be found in coastal areas of the world in small numbers such as the UAE, Oman, Malaysia and India.

Pic – Courtesy University of Pennsylvania

This here is a legend from Calicut, and was originally narrated by the great writer Kottarathil Shankunni in his magnum opus ‘Aithihyamala’ a brilliant collection of fables, folklore and legends of Kerala. While it is not factual history by itself, it tells you quite a bit about the times, and a little about the royal affairs of the Zamorin and the importance of legends & superstition in those times. I have tried to understand and analyze the story after re-narrating it in English, by adding some meat here & there to create better perspective for today’s readers.

We have all read so much about the words of the many travelers who wrote about Calicut. They called it a prosperous trading place, with honesty that prevailed and people who lived harmoniously despite the many religions, castes, nationalities etc. We have read much about the Zamorin and how he conducted his administrative tasks and patronage of arts in medieval times, we have heard about later colonialists and their accounts, some very exact and some grossly exaggerated. But this one is still folklore. I would assume that this is set in the 1760 AD time frame, a period when the city is doing well and trade was prospering. The Mysore Sultans had not yet arrived and the Dutch traders were quite localized in Cochin.

Let’s first look at another legend – of how it all started. A seafaring merchant reaches the coastal sands of Calicut - Kozhikode. During an audience with the sovereign, the Zamorin, the traveller requests that a consignment of jars filled with pickled food be entrusted with the royal house for safekeeping until his return from the next voyage. The merchant’s son returns the following year to reclaim them from the ruler’s custody. The king, knowing only too well that the jars had in fact contained hidden gold, returns the entire consignment untouched. The young merchant proclaims: “This is the harbour of honesty”. Word spread, trade flourished…

And so things were going well. The benevolent Zamorin was going about his work of reviewing his relationships with the neighboring principalities of Polanad, Kolanad, Valluvanad and sometimes troubled by the stances taken by the Cochin Varma’s and the Dutch rulers there (See my article on van Rheede ). The ‘mamankhom’ festival at Tirunavaya was coming up and the various assistants were gearing up for the pomp & splendor. The various Samoothiri (Zamorin) Kovilakom’s had their own subterfuges, quarrels between relatives and as Karanavar, the Thampuran (for that was how he was called in the family) had much to ponder on, mediate and order. Sometimes he got involved, sometimes he allowed his heir apparents the Eralpads (second in line) and Moonalpads (third in line) to take decisions. He had to be careful though and on the watch always, for you never knew who plotted against whom. He had to keep careful watch over the revenues from the ports around Calicut, and had to ensure that the Moplahs and Koyas kept full control over the trade and tendered the taxes & duties. Things had been getting a bit difficult with the Moplahs after the death of the Kunjali Marakkar.

As was the practice, the Zamorin’s palace had many scribes, the Menon’s recording all decisions and the karyakkar’s took care of the various petty issues and administration acts. Among the ministers, the principal revenue collector or Dewan was the most trusted among the lot in his retinue. He had to be a master of many languages, had to be very clever and be an excellent judge and arbitrator and have full control of the various junior ministers or Kariakkars. The reigning Zamorin in this instance was fortunate; he did have a good Dewan.

However, the Zamorin was distressed, for some time his right shoulder had been bothering him. The pain was becoming intense and any amount of massage, Ayurvedic treatments and ‘kashayams’ (herbal medicines) did not help. Many a local (Moosad) doctor had tried to find a cure, but the pain would not recede. Tantric’s and others tried, but of no avail. They all expressed that this was an incurable ailment, a ‘teeravyadhi’.

As days went by, the distress grew. The Zamorin was becoming listless and very much distracted by the pain. One fine day a youth appeared at the palace and stated that he had heard about the problem and may have a solution. The young man was summoned to an audience with the Zamorin. As he went in, he saw the Zamorin lounging on his easy chair chewing betel leaves and staring vacantly at the ceiling. The man asked briefly about the Zamorin’s illness and after listening patiently, said that he had a very simple solution. He said “respected sir, all you need to do is apply a wet Thorthu (towel) on your right shoulder for a while and everything would be set right’.

The Zamorin considered this for some time. As he had already tried all kinds of things, there was no harm in trying this rather silly experiment as well. The others in the palace who heard this were skeptical, but said nothing. So the Zamorin did exactly as the young man advised and lo and behold! The pain was gone in a jiffy. The Zamorin was very pleased and gifted the young man with a number of Parithoshikam’s (gifts) and a Veera Srinkala (Ankle bracelet).

On that eventful day, the learned Dewan was out traveling the region. When he returned later in the afternoon and heard the story of the miraculous cure of the Dewan, his suspicion grew. A young man from nowhere curing the ailment that other specialist had failed to cure? They had said that it was a ‘teeravyadhi’, one that would be with the old man until death. This did not look very good to him. When he learnt the details and the fact that the Zamorin had been made to apply his wet or “eeran” towel on his right shoulder, he knew exactly what had happened. He sensed not only danger to the Zamorin but also imminent disaster for whole kingdom.

He exclaimed ‘what a mistake’ and in great haste left the palace. He walked about for a while, looking at the people milling around and conducting various affairs of trade. Around dusk, he proceeded towards ‘Angadi area’ (big bazaar) or market area. Soon he spotted her, for she was standing alone in a corner as though waiting for somebody, and she did look out of place with her simple but elegant dressing, and her lovely high born appearance. But the Dewan had no doubts and had found her, just in time. Walking up to her, he informed her with great humility that he had a matter of great importance to discuss with her. Would she be prepared to listen? The lady graciously agreed, stating that she would of course be happy to listen to the Dewan. But natural I guess, for the Dewan was dressed in resplendent fashion, spotless dhoti and a well adorned turban. He was obviously a titled man from the palace, how could one refuse?

But the Dewan looked very flustered; he said “Oh, please madam, could you wait for a few minutes? I have forgotten my Mudra (palace seal) at the palace courts. Can I quickly go and get it? It is too dangerous to leave it lying around there. I have to pick it up and then come back to you and we will discuss the grave matter in a moment. Will you wait?”

The lady nodded in the affirmative, but the Dewan was insistent. He asked again ‘Will you promise me specifically that you will wait here till I come back?’ The woman promised that she would wait till he came back.

The Dewan went back to the palace with leaden feet and a tired countenance. He met the Zamorin and told him how grave a mistake he had committed. He explained that there was a good reason for the pain in his right shoulder; after all, it was Maha Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth & prosperity residing there and dancing on his shoulder. The family was prosperous, his luck was shining.

“This resulted in much prosperity for Calicut. What you have done, respected sir, is the most inauspicious and vile thing by putting a wet towel on the godess. By doing it, you drove her away and brought on the sister Bhaghavathy in her place. The situation was very clear to that clever youth and he used his knowledge to drive away the pain, but it is also going to bring you ill luck. Anyway, I have fortunately found a timely solution to the crisis. But it also means that I can live no more”.

Saying this, the Dewan swiftly left the Zamorin. Within the hour he took his life, killing himself by drinking poison.

It took a while for the events of the day to sink into the minds of the learned people of the palace. Much later, somebody explained them for the benefit of the public.

The Dewan had known immediately that the young man had done. The inauspicious deed was committed, now the only thing left to do was some ‘prathividhi’. Accordingly the Dewan set out to locate ‘Lakshmi’ the Goddess of prosperity. He saw her as soon as he entered the bazaar, for that is where her subjects are and that is where she wanders around, keeps an eye on their actions. By asking her to wait for him, getting the promise and killing himself, there was no way he was going to return. The Goddess had to keep her promise to remain where she was, that is, at the Agnadi or bazaar of Calicut, until the Dewan returned to talk to her.

And so there she remained, and there she remains to date and will for ever. It is said that the Calicut market takes a special hue in the evenings and is a beautiful place to see, for the Goddess graces the market in those hours. And that is the reason why the markets of Calicut have always remained prosperous. The Dewan had done justice to his title, he had with his actions and his very life ensured that the revenues will always be generated in the markets.

But the Zamorin had done the unthinkable; he had cast a wet towel on his right shoulder and driven away the Lakshmi from his personal life.

And so, as it was to happen, he lost the kingdom and position soon after.

Notes:

1. The first time the Zamorin lost his kingdom was when Hyder Ali attacked Calicut and the Zamorin took his life by committing the palace to flames. The Zamorin was from the Kizhake Kovilakom and died on April 27, 1766.

At that time, the Dewan Shamnath Pattar had not yet entered the scene. While that period of time is much talked about, the presence of another clever Dewan has not been recorded in other books. So the question remains, who could this Dewan have been? Certainly the origin of this legend remains murky.

4. The Aithihyamala was painstakingly compiled by Kottarathil Shankunny over a century ago. It is still a very popular book and has run over 22 editions. The book traces the cultural evolution of Kerala using legends and stories. During evening meetings at the Manorama newspaper office in Kottayam, K Shankunny, the poetry editor would regale his friends including Vargheese Mappila the owner of his

newspaper, with these stories. At Mappila’s insistence, Shankunni put them to paper first in a brief fashion for magazine publishing, then in a more detailed format, again after V Mappila asked him to do so. And that left us with this magnificent collection of tales. As Hindu explains - The work by Kottarathil Sankunni, which has not only influenced the imagination of the young and the old for the past one century but also emerged as one of the vital link for the new generation to the rich heritage of the Malayali society, has also remained one of the most loved books in Malayalam. I would earnestly request those who do not have this book to buy it and read it, for it will give you much pleasure.

newspaper, with these stories. At Mappila’s insistence, Shankunni put them to paper first in a brief fashion for magazine publishing, then in a more detailed format, again after V Mappila asked him to do so. And that left us with this magnificent collection of tales. As Hindu explains - The work by Kottarathil Sankunni, which has not only influenced the imagination of the young and the old for the past one century but also emerged as one of the vital link for the new generation to the rich heritage of the Malayali society, has also remained one of the most loved books in Malayalam. I would earnestly request those who do not have this book to buy it and read it, for it will give you much pleasure.ReferencesAithihyamala – Kottarathil Sankunni (Story#20 Kozhikottangadi)

Zamorins of Calicut – KV Krishna Iyer

Pic – Courtesy Hindu

Pantalayani Kollam, a port no more

Posted by Maddy Labels: Malabar - Portuguese, Malabar Pre 15th CenturyThough this port has been mentioned from very early times, it must have become popular some time after the 9th century and came to the forefront when two things happened, one being the move of the Arab & Chinese traders from Quilon & Cranganore to base their trade in Calicut, and the second when the Zamorin took charge. Since then it has been mentioned in many history books and accounts, though the names have varied slightly or largely. Today it is a small town that has been forgotten. Today it sits forgotten, bordering the more populated town of Koyilandi or Quilandy, housing one of the nine original mosques established by Malik Ibn Dinar. It is close to the historic Tyndis (Tanur or Thondi 3 miles north). The sacrificial rock , Balikallu or VelliyanKallu (white rock - Maris Erythrm of Periplus, Pai Chiao or Chia-Chia-Lu in Chinese) is right across (more on that another day) where many a soul was butchered, 3 leagues distant. Geographically, it is approx. lat. 11° 26', a little way north of Koyilandi.

Let us start by listing some of the different names used for this port that is shown as Kollam, to the North of Calicut, in a 21st century map posted here.

Fundaraina, Bandinanah, kandaraina, Bandirana, Fandarayna, Flandrina, Pandarani, Panderani , Pandalayani, Frandreeah, Fangarina, fandarain, Pandaramy, Pandarane, Fandreeah, Patale(Pliny acc to Logan), Pantalani, Panter Alandrina, Qandarina, Chulam, Pantar – In English & Portuguese books

, Pandalayani, Frandreeah, Fangarina, fandarain, Pandaramy, Pandarane, Fandreeah, Patale(Pliny acc to Logan), Pantalani, Panter Alandrina, Qandarina, Chulam, Pantar – In English & Portuguese books

In Chinese-Fan-ta-la-yi-na Pan-ta-Li, Tao Yi Chi Lio, Pan-ki-ni-na

This port has always interested me, though I have never visited the exact locale myself. It is a short distance, some 20 miles or ~30 km from Calicut city and in history this was a major port near Calicut. I had briefly referred to the place in the Kolathiri-Zamorin rivalry story under the post Revathi Pattathanam, and other blogs covering the visit of Chinese traders & Zheng He. However it has been a problem place in history, for its distance from Calicut has varied from 5 miles to 20 miles on the coast line in various accounts.

CKR also provides us the information about the location of a Zamorin palace there - The Calicut Granthavari records the demise of a Zamorin from Panthalayini Kollam in 1597 and the coronation of his successor at the same location. But the records do not mention 'Panthalayini Kollam'. Instead, the name mentioned is 'Ananthapuram'.

Pantalayani Kollam as I mentioned earlier figured in the ancient scandal that further alienated the Kolathir and Zamorin families. According to Sreedhara Menon’s ‘Survey of Kerala History’ the Viceroy (KVK Iyer states kinsman of Viceroy) of Pantalayani belonging to the Kolathunad family met & fell in love with a Thampurati of the Zamorin family during a visit to Calicut and thence eloped to Pantalayani. The enraged Zamorin attacked & captured the port area and then aimed his sights at the Kolathiri Raja. This shows that the place had much importance and was a sizeable and rich place in those times, providing revenue to the Zamorin.

In his book ‘History of Kerala’, KV Krishna Iyer mentions that Kollam has a significance which is that ‘Ko’ is king and ‘Illam’ is house or palace, so Kollam is the abode of the king. As you saw there was a Zamorin’s palace at Anathapuram in Kollam.

Iyer also opines that pearl diving was popular off the Pantalayani coast line in ancient times and there were many oyster beds present. He confirms that Jews may have been present there after 68AD. He quotes Nilakanta Sastri in stating that Chulam could have been either Calicut or Pantalayani Kollam which belonged to the Zamorin.

As it started, it was the 2nd greatest center of Jews (SS Koder). Prof Jussay also confirms the fact that a number of Jews resided there. Some believe that Ben Yiju, the Adenese trader even lived there. Was this really the hometown of Ben Yiju? Greek historian Roxani Eleni Margarti thinks so while Goitein is emphatic in identifying Yiju as a resident of Mangalore or Manjarur.

Pliny (78)

He mentions Patale as the destination of ships sailing the Hippalus winds, which according toLogan could have been Pantalayani.

Al Idris (1150)Fandarina is a town built at the mouth of a river which comes from Manibar, where vessels from India and Sind cast anchor." From Bana [Thana] to Fandarina is four days' journey. Fandarina is a town built at the mouth of a river which comes from Manibar [Malabar] where vessels from India and Sind cast anchor. The inhabitants are rich, the markets well supplied, and trade flourishing. North of this town there is a very high mountain covered with trees, villages, and flocks. The cardamom grows here, and forms the staple of a considerable trade. It grows like the grains of hemp, and the grains are enclosed in pods. From Fandarina to Jirbatan, a populous town on a little river, is five days. It is fertile in rice and giain, and supplies provisions to the markets of Sarandib. Pepper grows in the neighboring mountains..

W Logan asks in his Malabar manual, Did the Kotta river flow into the Agalapuzha and find an outlet into the sea at Pantalayani Kollam in those days? Not improbable. If you look carefully at today’s terrain you see no river mouth at Panthalayani Kollam. Korapuzha opens into the Arabian sea, a few miles is South of Kollam, between Talakulathur and Kappad.

Where is Jirbatan? Some historians think it was Cannanore. Sarandib is apparently Sri Lanka. In those days Malabar was Ma-pe-eul to the Chinese and Calicut was Ku-Li.

Ibn Batuta (1343)

Sates that it was one of the three principal ports and one where the Chinese ships moored during the monsoon. He states that it was a great fine town with many bazaars and gardens. The Musalmans occupy three quarters and each has a mosque.

Friar Odorico (Sometime between 1321-1330)

Mentions can be found in the reports of Friar Odorico De Pordenone (The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the ... By Richard Hakluyt Pg 412) who passed by around the period of 1330, he mentions pepper & trade at Flandrina. He also mentions that Christians and Jews reside there, warring frequently and that the Christians always won these wars. H ealso mentions crocodiles in the rivers. He mentions (like the Chinese dis in 1407) that people worshipped the ox and an idol that was half man, half ox. He talks of ‘narabali’ or people sacrifice and the ‘sati’ custom. He state sthat women drank wine, men dis not and that women shaved off their eye brows and eye lashes.

Abdul Razzak (1442)He mentions presence of Chinese bagchan in Calicut, calling the harbor perfectly safe, bringing merchants from every country. The town is inhabited by a considerable number of mussalmans, and pirates dare not attack the vessels of Calicut. In the harbor one may find everything one desired. However this is to be understood as the port of Calicut since he mentions sailing by the port of Bandirana, on his way to Mangalore. So by 1440 the port of Calicut is also quite popular.

Varthema (1505-1510)A day’s journey from Dharmapatanam, subject to the King of Calicut. This place is a wretched affair and has no port. The city is not level and the land is high. According to him, it is North of Kappad (Capogatto).

Barbosa (1516)

Calls the place Pandanare, and mentions Kappat (Capucate) nearby where there is a great port with many moors, many ships and where sapphires can be obtained on a strand.

Zainuddin Mukadam (1540-80)

States that Pantalayani became prosperous because of the Muslim population after explaining the visit of the Cheraman Perumal, then the building of the mosque by Malik bin Dinar etc. He mentions the boats from Pantalayani that went to fight with Cabral, the fighting with Portuguese at Pantalayani in 1524, the burning of the town and the Juma mosque in 1550, further attacks of the Portuguese etc.

Pyrard Laval (1607)

There are many marshes and salt pits to cross between Coaste and Caleecut, and two rivers to cross by boat, about a league from one of which is a very fine town which we passed at night called Coluote (P Kollam) where the Portuguese once had a fortress and a residency as at Calicut, but they have lost one as the other. I saw it as I passed for it was not altogether demolished; it was even stronger than that at Calicut.

Logan (1890-1900)Establishes that it is 2.5 miles North of Quilandy. He adds that this was where the EIC ship Morning star struck a mud bank and was wrecked in 1793. He points out that this was the mud bank that ‘supposedly’ protected Vasco Da Gama’s ship during the monsoon months of 1498. South of the Mohammedan burial ground is a small bay where ships could dock. Arabian ships used to call at this port if they were blown off course even in the 19th century and early 20th century. The Mecca trade was administered out of Pantalayanai Kollam.

Logan also mentions the fact that the bathing tank of the mosque at P Kollam had a granite slab temple inscription in ‘vattezhuthu’ signifying that it was a temple handed over to the Muslims to covert into a mosque. Close to this mosque, into the sea is a rock on which one can find a foot print chiseled in the rock (Velliyan kallu?). This is supposedly Adam’s footprint, a place where he stooped before going to Adam’s peak in Ceylon. He concludes by saying that both the temple and the footprint are of Jain origin.

Logan also mentions the fact that the bathing tank of the mosque at P Kollam had a granite slab temple inscription in ‘vattezhuthu’ signifying that it was a temple handed over to the Muslims to covert into a mosque. Close to this mosque, into the sea is a rock on which one can find a foot print chiseled in the rock (Velliyan kallu?). This is supposedly Adam’s footprint, a place where he stooped before going to Adam’s peak in Ceylon. He concludes by saying that both the temple and the footprint are of Jain origin.

Note here that Quilandy or Kovilkandi had a separate port and here was where the pilgrims to Makkah embarked on their sea voyage. The Cheraman Perumal embarked to Makkah from Poyanad (Polanad?)after spending a day at Pantalayani Kollam! Later his written instructions from Arabia asked people going to Malabar to land in Quilon, Pantalayani Kollam or Kodungallur (Muziris).

According to Logan, one view now disputed, the Kollam era is related with the Kollam at Pantalayani due to the deduction that the Kollam year started with the sailing away of eth Cheraman perumal from those shores to Makkah.

Portuguese times 1498-1600

Starting from the time the Zamorin (residing at that time in the Ponnani palace) recommended that Vasco D agama take his ship to the safety of the mud banks in Pantalayani Kollam, the port of Pantalayani Kollam figures in numerous books and accounts. In most of these cases, the town is sacked or attacked by the Portuguese or the Moslem ships set forth from Pantalayani and Ponnani. They also mention of Kunhali Marakkar launching many attacks from this port. Many accounts describe the heavy rains that lashed the town when the Gama was returning from the audience with the Zamorin and how he failed to find his quarters etc.

About a third of the Moslems living there have lost their life in fights with the Portuguese according to Logan. There is a general belief that the Marakkars, the Zamorin’s admirals were settled in Pantalayani Kollam (See my blog on marakkars) before they moved to Kotakkal.

Chinese

Wang Dayuan was the first to mention the availability of precious stones at Fandarina. This was in 1349. Asia's maritime bead trade By Peter Francis (pg 123) mentions that the port was frequented by Chinese traders. Once Chinese trade declined, the port also started to fall apart until Varthema’s visit when he pointed out that it was a miserable place.In those days Malabar was Ma-pe-eul to the Chinese and Calicut was Ku-Li. Mongol dynasty documents of 1296 state that it was prohibited to export more than 50,000 ting in paper money worth of goods to Maprah (Malabar), Peinan (Malaya?) & Fantalaina.

Sankey (1881)

Letter from Col R. H. Sankey, C.B., R.E., dated Madras, 13th Feb, 1881: "One very extraordinary feature on the coast is the occurrence of mud-banks in from 1 to 6 fathoms of water, which have the effect of breaking both surf and swell to such an extent that ships can run into the patches of water so sheltered at the very height of the monsoon, when the elements are raging, and not only find a perfectly still sea, but are able to land their cargoes. Possibly the snugness of some of the harbors frequented by the Chinese junks, such as Pandarani, may have been mostly due to banks of this kind? By the way, I suspect your 'Pandarani' was nothing but the roadstead of Coulete (Coulandi or Quelande of our Atlas). The Master Attendant who accompanied me, appears to have a good opinion of it as an anchorage, and as well sheltered.

References

Hobson Jobson Dictionary

Malabar manual – W Logan

History of Kerala – KV Krishna Iyer

Tuhfat Al Muhahidin – Zainuddin Makhdum

The Jews of Kerala – PM Jussay

US Navy Map – Sacrifice rock to Beypore 1944

Ludovico di Varthema (1470-1517) is a well known Italian traveler and adventurer. Nearly everything that is known of the life of Ludovico di Varthema comes from his own account. Evidently a native of Bologna and a soldier, he left a wife and child in 1502, when, slightly over the age of 30, he left to visit the East. An independent source reveals that he was in Venice in November 1508 relating his adventures to the Signory. Nothing more is known of him other than that he spent his remaining years in Rome and was referred to as dead in June 1517. His travel book, Itinerario de Ludovico de Varthema Bolognese …, was published at Rome in 1510.

Richard Francis Burton said - For correctness of observation and readiness of with Varthema stands in the foremost rank of the old Oriental travelers. In Arabia and in the Indian archipelago east of Java he is (for Europe and Christendom) a real discoverer. Even where passing over ground traversed by earlier European explorers, his keen intelligence frequently adds valuable original notes on peoples, manners, customs, laws, religions, products, trade, methods of war.

Richard Francis Burton said - For correctness of observation and readiness of with Varthema stands in the foremost rank of the old Oriental travelers. In Arabia and in the Indian archipelago east of Java he is (for Europe and Christendom) a real discoverer. Even where passing over ground traversed by earlier European explorers, his keen intelligence frequently adds valuable original notes on peoples, manners, customs, laws, religions, products, trade, methods of war.

Varthema’s visit to Arabia and India is considered to be a fine document, providing if not accurate in specifics, detailed general accounts of social life in the places he visited. While most travelers concentrated on the wars, the relationships and the rulers themselves, Varthema talked extensively about the life in the locales he frequented, and keen understanding based on his claim to have mastered most of the tongues of the said places.

He is probably the only medieval traveler who has quoted Malayalam sentences or what purports to be Malayalam in his writings. Let us see what he has to say in Malayalam, hastening to inform here that this was just one of the many historians (another was Ibn Batutah) who was particularly interested in the sexual relations practiced by the inhabitants of Malabar. However he probably carried the ruse too far when he claimed to have understood and documented the same tongue Malayalam in far away Orissa or Andhra Pradesh (MachiliPatanam) unless of course he chanced on a Marakkayar Moplah visiting the port. Let us look at this famous and oft quoted paragraph which shows how absolutely ludicrous it is (like his chapter of his providing medical service at Calicut) and what a stupid image it provides to an avid reader not otherwise familiar with Malabar.

Varthema gives flight to his Malayalam fantasies twice in his accounts, once while accounting his first visit to Calicut and once while visiting Tarnassari (presumably Masulipatanam or Machilipatana where of course Malayalam was never spoken – Read on and take in a lot of mumbo jumbo which actually is absolute rubbish save a couple of words.

The original account, in Italian, was published at Rome on the 6th December 1510 at the request of Lodovico de Henricis da Corneto of Vicenza by Stephano Guillireti de Loreno and Hercule de Nani, both of Bologna. The translation used here was made by John Winter Jones in 1863, edited by G. P. Badger, and published under the title of “The Itinerary of Ludovico di Varthema of Bologna from 1502 to 1508”.

QUOTE

Calicut

Pg 145, 146, 147 - The Pagan gentlemen and merchants have this custom amongst them. There will sometimes be two merchants who will be great friends, and each will have a wife; and one merchant will say to the other in this wise: " Langal perganal monaton ondo ?" that is, " So-and-so, have we been a long time friends ? " The other will answer: " Hognan perga manaton ondo ;" that is, " Yes, I have for a long time been your friend." The other says: "Nipatanga ciolli ? " that is, " Do you speak the truth that you are my friend ? " The other will answer, and say : " Ho ; " that is, " Yes." Says the other one: "Tamarani ? " that is, " By God ? " The other replies: " Tamarani ! " that is, " By God ! " One says: " In penna tonda gnan pcnna cortu; " that is, " Let us exchange wives, give me your wife and I will give you mine." The other answers: " Ni pantagocciolli? " that is, " Do you speak from your heart ? " The other says: "Tamarani!" that is, " Yes, by God!" His companion answers, and says: " Biti banno ; " that is, " Come to my house." And when he has arrived at his house he calls his wife and says to her: " Penna, ingaba idocon dopoi ; " that is, " Wife, come here, go with this man, for he is your husband." The wife answers: "E indi?" that is, "Wherefore? Dost thou speak the truth, by God, Tamarani?" The husband replies : " Ho gran patangociolli; " that is, " I speak the truth." Says the wife: " Perga manno ; " that is, " It pleases me." "Gnan poi;" that is, " I go." And so she goes away with his companion to his house. The friend then tells his wife to go with the other, and in this manner they exchange their wives; but the sons of each remain with him.

(JOHN WINTER JONES the translator’s note - I had hoped to have been able, by the assistance of others, to reduce this and the subsequent native words and phrases introduced by Varthema into readable Malayalam, in the same manner as I have treated his Arabic sentences; but the attempt has proved unsuccessful. Two Malayalam scholars, to whom they were submitted, concur in forming a very low estimate of our traveler’s attainments in that language. One of the gentlemen states that the majority of the words are not Malayalam, or, if they are, the writer has trusted to his ear, and made a marvelous confusion, which I defy anybody to unravel." This is not to be wondered at; on the contrary, there would have been reasonable ground for surprise if, under his peculiar circumstances, Varthema had succeeded in mastering, even to a tolerable extent, any one of the native languages.