The Achans of Tarur Swaroopam, the Edams of Palghat, and the events which prompted Hyder’s intervention

Some months ago we touched upon the topic related to the

ancient royalty of Palghat. We covered the Palghat Achans and the Kollengode

nambis briefly. As a number of requests came in for more detail on the history

of the Palghat Achans, I decided to delve a little deeper, armed with details

that I had collected from a few sources.

We start by covering some recorded descriptions. The

following description of the Palghat royal family was given in Mr. Warden's

report to the Board of Revenue dated 19th March, 1801 :-

"It originally

consisted of eight Edams or houses equally divided from each other by the

appellation of the northern and southern branch The members of these Edams are

called Atchimars, five of whom, the eldest in age, bear the title of Rajahs,

under the denomination of the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th and 5th Rajahs, ranked

according to their age, the senior being the first. On the death of the 1st

Rajah, the 2nd succeeds and becomes the senior, the 3rd becomes 2nd, and so on

to the 5th, the vacation of which rank is filled by the oldest of the

Atchimars. By this mode of succession, the eldest Rajah is very far advanced in

years before he accedes to the seniority, in consequence of which it used to be

customary to entrust the ministry of the country to one of the Atchimars chosen

by the Rajah.

The eight Edams of

Atchimars above mentioned multiplied so numerously in their members that they

afterwards divided and formed themselves at pleasure into separate Edams, which

they distinguished by their own names. The number now in existence consists of

twenty-seven, of which twenty belong to the northern and seven to the southern

branch. The number of Atchimars they contain including minors is about one

hundred and thirty ".

You will now need to note that by the 18th

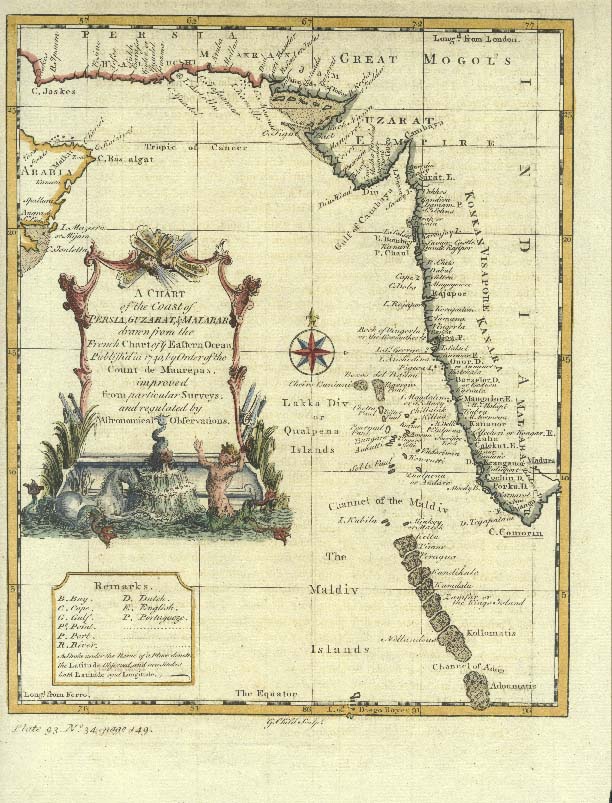

century, there were 35 Principalities (Naads) in Malabar which are listed as:

Kottayam (Malabar), Kadathanad, Kurumbranad, Tamarasseri-Wynad, North

Parappanad, South Parappanad, Valluvanad, Vadamalapuram, Tenmalapuram,

Kolathunad (All ruled by Samanta Kshatriyas); Polanad, Payyanad, Ramanad,

Cheranad, Nedunganad, Naduvattam, Kuttanad, Chavakkad, Chetwai, Eranad,

Neeleswaram, Konad, Kodikkunninad, Vettattnad, Kakkad, Beypore, Talapilli,

Chirakkal, Kollamkode, Punnathur (All ruled by Samantan Nairs); Kavalapara,

Kurangott, Payyurmala, Pulavai (All ruled by Moopil Nairs). We will be talking

about the overlordship of three of them, in the Palghat region.

But let us get to some basics first. Some 10 km away from

Alathur is the place called Tarur. How did the Swaroopam or royal family of

Palghat get its seat rightly or wrongly connected to this place? Taru, Taravayur,

Taravur and Tharoor are synonyms for the Swaroopam that can be seen mentioned in

various sources. Looking at the Oriental library Granthas 263 & 266, we see

the following - The name of the land was mentioned as Nedumpuraiyur and earlier

as Taravayur – or Devalokesharajya in the times of the Cherman Perumal who is

so deeply connected to mediaeval Kerala History. It was only much later that

the location Tarur which was just one of the edoms intermingled with the old

name of the region and the family and was considered a seat of the family (wrongly).

The region is even considered to have been part of the Chera kingdom in ancient

times and a part of the Perumal’s territory.

The rulers of Palghat it seems originated from the

Athavanaad Amsam in Ponnani. For some

obscure reason they traded their original lands with the Azvancheri thampurans

who gave them Palghat in return, a very strategic location due to the importance

of the Palghat gap among the trade routes to the western ports. They are

mentioned in the Rabban plates and at that time, Palghat also included the

Talapilly taluk. There are also other rumors that they originated from Madurai but

we also note that they were closely related by marriage to the Perumbadappu

Swaroopam or the Cochin royals. The family did not really gain any sort of overriding

importance in the Malabar events until the 18th century and when

they did enter into it, it was to pave the way for the destruction of the old fabric,

the ways and the practices of the land.

We will get to all that a little later.

As times went by, the splits in the family occurred owing to

the kings relations with a non-Kshatriya woman resulted (read the earlier

article). Two of the Kshatritya women from the family marrying Namboothiris

went on to start the Vadamalappuram and Thenmalapuram family lines. The

resulting families, many hundreds of them were aligned either to the northern

or the southern factions. The various resulting Edoms were

Southern faction (Thekke Thavazhi)

Elayachan edom

Vadakke

eleyachan edom

Thekke

eleyachan edom

Paruvakkal edom

Vadake

Paruvakkal edom

Thekke

Paruvakkal edom

Akkare

Paruvakkal edom

Northern faction (Vadakke Thavazhi)

Cherukottar (Cherukotham) edom

Pulikkel edom

Vadakke

Pulikkel edom

Thekke

Pulikkel edom

Maruthingal

Pulikkel edom

Puthal

pulikkel edom

Mel Edom

Malikamel

edom

Kolamkulangurmel

edom

Kizhakkemel

edom

Tatchadmel

edom

Vellambalaikkalmel

edom

Vadakkmel

edom

Valiyamel

edom

Chitlanjerimel

edom

Poojakkal edom

Konikkal edom

Valiya

konikkal edom

Kizhakke

konikkal edom

Tharoor

konikkal edom

Kavasseri

konikkal edom

Nellikkal

edom

As is evident, only the Tharoor Konikkal edom maintained the

original family name for some unknown reason. By the 19th century the northern

branch had 20 families and the south seven. By 1879, the royal family count was

roughly 519. They were also called the Shekhari varams or Shekari rajas.

Every Swaroopam maintained the structure and control with

their Nair numbers. More the Nairs available for a fight, the more powerful

they were. In that old principality, the chieftains exercised control over

8,000 Nair soldiers in the following fashion. Tenmalapuram contributed 3,000,

Naduvattom 3,000 and Vadamalapuram with 2,000. You may of course recall the

name Naduvattom which is towards the South eastern periphery of Palghat, and

this was the area that was to become a bone of contention between the Paghat

Raja and the Zamorin of Calicut.

With this background, let us join Francis Hamilton Buchanan

who made some of the earliest accounts of Palghat.

I went a long stage to

Pali ghat. The country through which I passed is the most beautiful that I have

ever seen. It resembles the finest parts of Bengal; but its trees are loftier,

and its palms more numerous. In many places the rice grounds are interspersed

with high swells, that are crowded with houses, while the view to the north is

bounded by naked rocky mountains, and that to the south by the lofty forests of

the Travancore hills. The cultivation of the high grounds is much neglected.

Pali-ghat-shery, on

the division of Malayala, fell to the lot of Shekhury Raja, of the Kshatriya

cast; but as this family invited Hyder into the country, they are considered by

all the people of Malabar as having lost cast, and none of the Rajas of Kshatriya

descent will admit them into their company.

To a European the

succession in this family appears very extraordinary; but it is similar to that

which prevails in the families of all the chiefs of Malayala. The males of the

Shekhury family are called Achuns, and never marry. The ladies are called

Naitears, and live in the houses of their brothers, whose families they manage.

They have no husbands; but are not expected to observe celibacy, and may grant

their favours to any person of the Kshatriya cast, who is not an Achun. All the

male children of these ladies are Achuns, all the females are Naitears, and all

are of equal rank according to seniority; but they are divided into two houses,

descended from the two sisters of the first Shekhury Raja.

The oldest male of the

family is called the Shekhury, or first raja; the second is called Ellea Raja,

the third Cavashery Raja, the fourth Talan Tamburan Raja, and the fifth

Tariputamura Raja. On the death of the Shekhury, the Ellea Raja succeeds to the

highest dignity, each inferior Raja gets a step, and the oldest Achun becomes

Tariputamura. There are at present between one and two hundred Achuns, and each

of them receives a certain proportion of the fifth of the revenue that has been

granted for their support, and which amounts in all to 66,000 Viraraya Fanams a

year, but one sixth part of this has been appropriated for the support of the

temples. Formerly the whole was given to the head of the family; but, it having

been found that he defrauded his juniors, a division was made for each,

according to his rank; and every one receives his own share from the collector.

(Note that this was written in 1807 and Thomas Warden then was district

collector)

Every branch of the

family is possessed of private estates, that are called Chericul lands; and

several of them have the administration of lands belonging to temples; but in

this they are too closely watched by the Namburis, to be able to make any

profit. The present Skekhury Raja is a poor looking, stupid old man, and his

abode and attendance are the most wretched of any thing that I have seen,

belonging to a. person who claimed sovereignty. His principal house, or Coilgum,

is called Hatay Toray, and stands about three miles north from the fort.

We note that during the 13th century, the Palakkad royal

family had no male heir to succeed to the throne and only two Tampurattis or

princesses of the royal blood remained. These princesses therefore cohabited

with the chosen two of the Perumpadoppu Swarupam at the Vadakknathan temple at

Trichur after some serious praying. Progeny were created and the line

continued. The succession of Tarur Swarupam was thus maintained through these

alliances. As compensation, the region around Kunisseri became part of Cochin,

together with the Nair’s of the region. But as the tale goes on to state, this

land was retaken by the Palghat rajas later.During this period the relation

between the Raja of Perumpadappu and Tarur Swarupam was maintained in a cordial

fashion and in the war between Zamorin of Kozhikode and the Raja of Cochin, we

see that the Palakkad rajas sided with the Cochin kings.

KVK Iyer explains that the original family seat and shrine was

near the Victoria College location. The formal accession of a new head takes

place here and then they proceed to the banks of the Bharatapuzha termed

Tirunilakkadavu for standing in state.

One other matter of interest is the battle between the

combined forces of Malabar (which included the troops of the Zamorin) against

the Vijayanagar forces led by Ramappayyar and Devapayyar at Palghat and I had detailed

it separately in an earlier article. During this and after this event many forts of

Palghat were destroyed including the old Tarur Kovilakom. The ancient forts at

Akathethara were built following this event. Readers must not confuse these mentions with the massive

granite fort you can even now see in Palghat, but they were small mud fortifications

at strategic locations. In later days many lakkidi kotta’s or wooden forts were

constructed by the Mysore forces.

With this brief introduction, I will now continue with the

18th century situations that prompted the invasion of Naduvattom by

the Zamorin and the arrival of Hyder. We will get to that story in greater

detail, for there was not much detail mentioned in the popular history books other

than the invitation of Hyder by the Kombi Achan of Palghat after the Zamorin

invaded Naduvattom. Well, there is more to it than meets the eye!! And so we

now traverse down to the year 1756-57.

In 1755-56, after the demise of the raja from the Cherukotha

Edam, the raja from the Elayachan edam named Raman Kombi took over. It was

during his reign that the Zamorin sent out his forces headed by the Chencheri Namboothiri

( Aiyers accounts mention the Zamorin’s son – the Kuthiravattom Chief as the head

of this operation) to take over Naduvattom in 1757. Some geographical knowledge

is a must and interestingly this is where my maternal family had settled down.

Vadavannur, Palassena, Erimayur, Koduvayur, Manjalur, Kozhal mannam, Pallasena

etc…, formed part of the Naduvatton area which the Zamorin forces eventually captured

to trigger panic among the Palghat Achans. Aiyar mentions that they came

through Pattikad and descended on vadakancheri and Trippalur and detoured to

Kollangode. The Kollengode nampi submitted to the Zamorin quickly. The

Kuthiravattom Nair then built a fort at Koduvayoor (the present town was formed

after this event).

But let us continue with what we see in the Grantha - The

Namboothiri was vicious in his execution of the order. He raided the area –

comprising the Kavasseri and Pulikkel Edams as well as the Vadakachery

Puzhakkal Edam and took them over. Bereft of leadership, the Tenmalapuram 3000 nairs

decided to put closure to the situation by paying a reparation fee to the

Zamorin amounting to a fifth of the total claim and suing for peace. The

Chencheri namboothiri next trained his guns at Palghat and marched to the Yakkara

banks, while Ittikombi atchan, nephew of the Elayachan Edam raja prepared for the

attack with the Vadamalapuram 2000 nairs. A terrible fight took place where

over 5000 were killed and the Chokanatha puram fort was taken over. As a

result, the various remaining members in the Palghat Edams fled to Coimbatore

and decided to approach the Coimbatore king Shankar raja for assistance. Peace

was negotiated in the meantime by the Tiruvalathur Koikkatiri for another fifth

of the reparation war expense claim. This amounted to 1/4th viraraya

fanam per para of paddy during the harvest.

The Zamorin now paused and instead of moving northwards to

Palghat saw a golden opportunity in Cochin where an opportunity presented

itself due to other struggles. It appears that the Zamorin was victorious there

and succeeded in obtaining large reparations from the Cochin kings in this

effort. Not only did the overtures against the Palghat rajas grant him access

to the rice lands of Palghat, but also the Kuttanad regions after the success at

Cochin.

As it is stated in the grantha, the Pangi Achan (nephew of

elayachan edam thampuran), Kelu achan of Pulikkel edam and a few of the

important regional heads travelled to Coimbatore to meet the Sankara Raja who

gave them known emissaries to accompany them to Srirangam (Mysore –

Srirangapatanam) to meet the Dalawa there. From there they were redirected to

meet Hyder Ali who was the Faujedar or commander in chief of the infantry at

Dindigul, nearer to Palghat. Hyder then deputed his brother-in-law Muquadam Ali

with his forces to Palghat. This resulted in a severe war with the Zamorin’s

forces in Feb 1758 where the Mysore forces were victorious. Muqadam Ali’s forces withdrew after collecting

their compensation by way of gold melted out of the ornaments worn by the Emoor

bhagavathi (the tutelary deity of the Palghat Achans), as rakshabhogam (equivalent

of 12,000 old Viraraya fanams). The Zamorin it is said (not in this grantha

though, but in British records) apparently sued for peace by promising to pay

12,00,000 fanams as reparation.

After the Mysore forces had left with their booty, the

Zamorin’s forces visited Palghat to collect their previously agreed war

reparation costs from the Palghat edoms. As negotiations were going (this was

in 1760) on at Vaidyanathapuram, some 2,000 people surrounded the area and many

of the elders of the Palghat edoms were massacred. Interestingly none of the

records identify the perpetrators of the treachery or lay it at the doors of

the Zamorin. The rest of the Palghat royals including the women fled to

Coimbatore again through the dense forests. Sankara raja provided them asylum

and Panki Achan and Kelu Achan went to Mysore to meet Hyder who had by then

worked his way to take over the Mysore throne. However in all this the Mysore

sultan profited greatly, not only getting reparations from the Palghat Raja,

but also a promise from the Zamorin. The Zamorin’s reparation expenses as

previously agreed was never met by the Paghat raja.

It is stated in other records that a Zamorin emissary met

Devaraja of Mysore in the meantime and agreed to pay a reduced reparation of 3

lakhs instead of the 12 lakhs claimed by Hyder, This was agreed by Devaraja,

but he was soon usurped by Hyder who refused to accept Devaraja’s agreements

with the Zamorin. It was with this backdrop that Hyder proceeded to Mangalore

with 12,000 troops and invaded Kolathunaad and later Calicut with a stated aim of

collecting the 12 lakhs from the Zamorin. This quickly degenerated into the

suicide of the Zamoirn in 1766 which we detailed earlier.

Following this, the Palghat ruler Kelu Achan was removed

from his position and Ittikombi Achan was appointed ruler by Hyder and after an

agreement to pay him 4 lakhs per annum. Hyder Ali moved to Coimbatore, displaced

the Coimbatore raja and took over his palace. That was what Coimbatore raja got

for supporting the Palghat raja. Following this the now famous fort was

constructed at Palghat, we mentioned it briefly in another article.

The situation never improved for the Ittikombi achan’s

descendants. A number of succession struggles took place, and we see the

attempts of Kelu Achan in trying to wrest the power out of the Ittikombi Achan’s

hands. More wars took place involving the British at Palghat. Hyder passed on

and gave the reins to Tipu, who continued with warring efforts. It seems that

when Haider took a stronghold over Palghat later, the Kallekulangara family

moved to Kallekulangara. During Tipu’s arrival the dietey was saved in a pond

and the family apparently took to the hills. During the British occupation, the

diety was reinstalled in the shrine.

By 1790 the victors were the British and the Mysore Sultans

gave way to another new order in Malabar and Palghat. By 1792, the Palghat

Achan had to bargain with the British to maintain his title and signed a treaty

with the EIC where he ended up paying 80,000 per annum to them instead! We see

then that by 1794 that titular position was also lost and the Achan became a

pensioner with just an annual malikhana. The roughly 1000 year old family thus

slowly descended to pensioner staus like most of Malabar’s other royals, after

leading lives sandwiched between the Zamorin and the Cochin king. Their choice

of treacherous allies ultimately paved the way for the Mysore Sultans

victorious march into Malabar.

In the next article we will dwell upon the British attempts

at taking strong control over Palghat and study the role of Unni Moosa Moopan.

References

Oriental Manuscripts – Madras Library – D266, 263 –

Malayalam transcript by KN Ezhuthachan

Kerala District gazetteers - Palghat – Dr CK Kareem

Malabar Law and custom – Lewis Moore

A journey from Madras through the countries of Mysore,

Canara and Malabar Vol 2 – Francis Hamilton Buchanan

History of Kerala – KV Krishna Ayyar